“Skepticism Has Grown”

Policy analyst Jan Hofmeyr on the legacy of Nelson Mandela, the diluted social capital of the ANC – and why migration is a challenge for South Africa.

BTI Blog: South Africa is in mourning, having lost the great inspirational and integrative personality of Nelson Mandela. What has changed since – has he given your country one last integrative impulse as it is united in grief, or will he be missed as the great consensus-builder so that societal rifts and cleavages will become more visible again?

Jan Hofmeyr: To link the political stability of South Africa to the personality of Mandela is to miss his greatest legacy to the country: that we will not again need another Mandela to save us from the brink. Despite many gains, the social rifts and cleavages that existed under former President Mandela’s presidency still exist today. Although no longer legislated, the color of your skin very often still plays a determining role in the opportunities that can be accessed. Others, like class inequality, have become even more pronounced since the advent of democracy. Separately and combined they still exert major pressure on the fiber of the post-apartheid state. But the South Africa of today is not the South Africa of 1994, where the legitimacy of the new political dispensation hinged on the personalities of a few, rather than a set of legitimate public institutions, guided by a constitution, and upheld by an independent judiciary, as is the case today. These institutions are young and their capacity do on occasion come under strain to deliver more rapidly on huge developmental backlogs. Too much of their resources are also drained by corruption and maladministration. In instances where their independence have come under threat, the judiciary, and vigilant media and civil society have provided an effective counter balance to the encroachment of state power. Challenges there are many, but we are infinitely better equipped to deal with them today than we were 20 years ago. Nelson Mandela was indeed a unifying figure. Mandela’s extraordinary contribution during his presidency was to instil a sense of loyalty, detached from his own persona, to the new state, which continues to supersede race and class schisms to this day. South Africans from all backgrounds referred to him as Tata (father). But like all good fathers, he ensured that his children were self-sufficient and capable to deal with their own challenges when he is no longer.

BTI Blog: More than two decades have passed since the end of apartheid, and South Africa is often cited as a role model for reconciliation. What is your estimation of this process? And is it complete?

Jan Hofmeyr: Reconciliation cannot imply a process where increasingly more citizens “forgive or forget” the country’s past. Given the scale of oppression most South Africans experienced under apartheid, this would set the bar too high. Reconciliation entails a growing acceptance of our interconnectedness and a commitment to creating a common future. Under former President Mandela’s leadership, this understanding of reconciliation took precedence to ensure that the rebuilding of the country could occur in an environment unencumbered by potential spoilers. Yet, in the past 13 years, skepticism has grown as the promised outcome, the creation of a better life for the majority, has proven difficult to achieve. Although the country’s middle class is slowly becoming more integrated, race continues to figure strongly in poverty and inequality. While poverty levels have dropped, inequality has widened. There has also been a perception that a large component of white South Africans have disengaged from the process of rebuilding the country.

BTI Blog: South Africa represents one of the few success stories on the African continent. Equally established are the merits of the African National Congress (ANC), which has been the dominating political force since 1994. But the BTI country report notes a “widespread dissatisfaction” with the ANC. What are the roots of dissatisfaction – and is it justified?

Jan Hofmeyr: The ANC still describes itself as a liberation movement, but growing numbers of younger South Africans evaluate its performance in government, not its legacy. Although millions of South Africans are now better off, many believe the government could have done better with the resources and political power at its disposal. Much of this can be attributed to policy inconsistency resulting from power struggles within the ruling tripartite alliance of the ANC, the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and the South African Communist Party (SACP). Growing evidence of government corruption has also diluted the ANC’s social capital. But dissatisfaction has not resulted in major electoral defeats; many of the ANC’s former voters have simply abstained from voting and have not yet found an alternative political home.

BTI Blog: South Africa invests almost six percent of its GDP in education, which is more than the EU average. Why are successes few and problems still massive?

Jan Hofmeyr: First, there have been historical inequalities to address. Second, the continued impact of poverty on the ability of students to perform cannot be underestimated. A hungry child is unlikely to perform, even with the best infrastructure. Third, compared with EU countries, South Africa has a much younger population (72% is under the age of 35). Proportionally, the South African education system has far more students, which results in lower levels of spending per child. Finally, the current government has been inefficient and sometimes wasteful in spending its allocated budget. In 2012, students in some provinces did not have access to textbooks, while thousands of dumped textbooks were found in remote areas.

BTI Blog: The National Development Plan intends to cut unemployment to six percent by 2030, just a quarter of its current rate. How realistic is such a goal, and will it become easier or more difficult to reach a consensus on development goals in the years to come?

Jan Hofmeyr: This will be difficult to achieve under current circumstances, as GDP will have to grow at an annual average rate of 5.4 percent. In the past two years, it failed to reach even three percent. External circumstances will therefore have to align with the internal measures taken in this regard. But some of the biggest unions within COSATU have rejected the entire plan outright or parts of it. Such fragmentation within the alliance will slow the plan’s implementation.

BTI Blog: The comparatively rich South Africa is a popular destination for inner-African migration. Migrant workers represent additional competition for scarce jobs, and xenophobia is growing. How should the government deal with illegal immigration, migrant workers and growing militancy?

Jan Hofmeyr: Migration to South Africa will remain an inevitable reality. The government will have to become more proactive in this regard. Better regulation instead of forceful suppression is needed. The country’s porous borders make tracking migrant movement difficult. High levels of corruption and intimidation by police toward foreign migrants further undermine the migration system. In recent years, the Department of Home Affairs has also reduced the number of locations where migrants could obtain the required documentation to stay in South Africa and, as a result, migrants have logistical difficulties in registering. The greatest challenge lies in educating South Africans about the context of migrancy and migrants’ rights. Successive surveys have pointed to high levels of prejudice toward migrants among South Africans of all classes. Much more needs to be invested in educating citizens in order to pre-empt xenophobic violence.

Jan Hofmeyr heads the Policy and Analysis Programme at the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation (IJR) in Cape Town. The institute, a recipient of the 2008 UNESCO Prize for Peace Training, focuses its activities on matters of transitional justice within African societies. Jan Hofmeyr has contributed to the Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI) and the Sustainable Governance Indicators (SGI). Before joining the IJR, he worked with the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung’s Democracy Development Programme in South Africa. Jan Hofmeyr has been a member of the Transformation Thinkers network since 2005.

Interview: Hauke Hartmann

Related BTI

Study: BTI 2014 Report

Political Management in International Comparison

Related SGI

Study: Governance in the BRICS

How sustainable is governance in Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa?

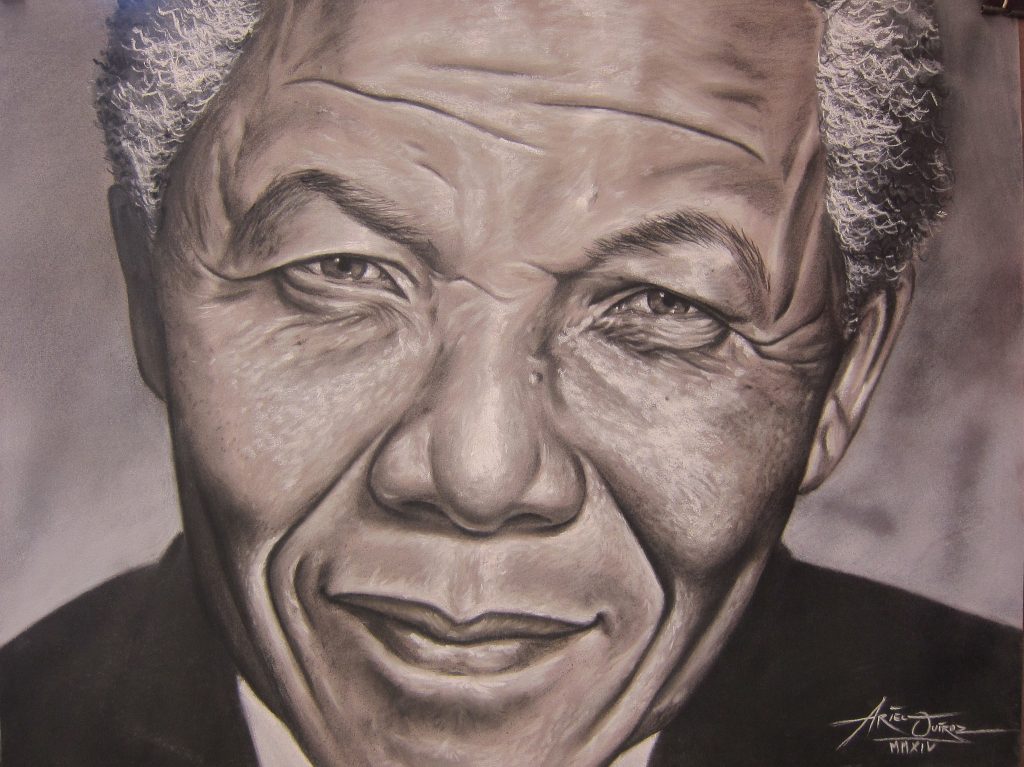

Photo: Nelson Mandela, by Ariel Quiroz, via flickr.com, CC BY 2.0