Democratic Neighbors as a Challenge to Autocratic Narratives

Over the past ten years, the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) has identified considerable declines in the quality of democracy worldwide. Significant downturns have been recorded in all core institutions of democratic governance. More than a quarter of all 137 countries in the BTI declined markedly on a 10-point-scale in their status of political transformation during the past ten years, by 0.75 points or (much) more.

Bad democratic governance and the tale of autocratic superiority

It is important to remember that these political regressions did not take place in a vacuum. Whereas autocratic hardening followed a regime logic to stay in power at all costs, as recently seen in Belarus, political regression in democracies was ultimately caused by bad governance. Blatant mismanagement and unfulfilled promises of economic and social inclusion were often the reason for voters to choose the authoritarian populist card, as in Brazil or Hungary. Also, bad democratic governance not only had a corrosive effect on the stability of democratic institutions and the approval of democracy on a national level, but it also eroded the trust in democracy as a guiding principle for societal transformation.

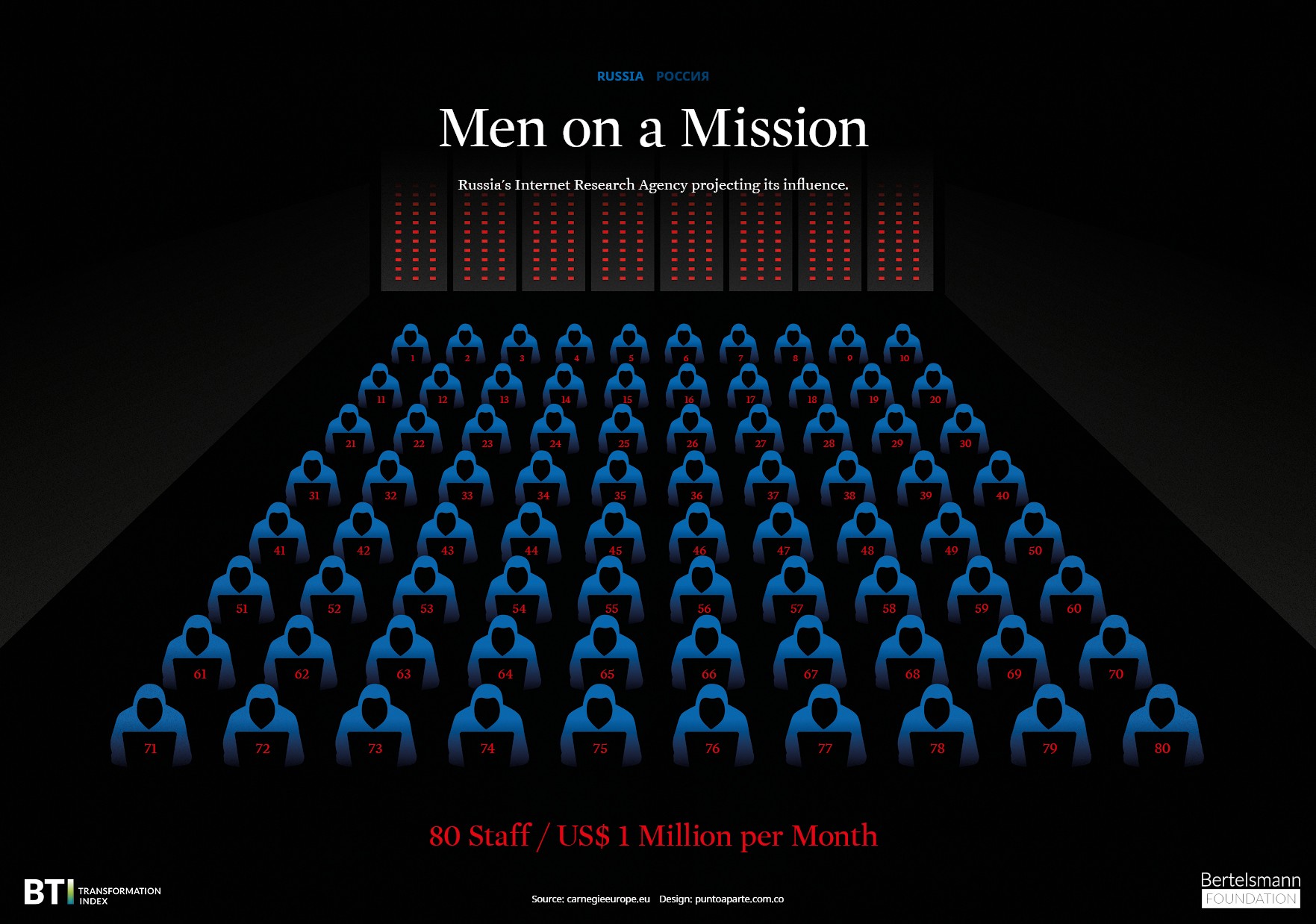

It is exactly this failure of democratic governance to deliver that is picked up by Chinese propaganda. While also the Kremlin didn’t spare any efforts to subvert democratic discourse in open societies by discrediting elections and spreading fake news, this was more directed against alleged Western aggression and decadence.

The Chinese approach, however, thematizes autocratic superiority. It used to be more subtle but grew increasingly blunt in recent years, especially around and after the 19th party congress in 2017. A commentary published by the state news agency Xinhua at that time held that “crises and chaos swamp Western liberal democracy,” whereas “[t]he Chinese system leads to social unity rather than the divisions which come as an unavoidable consequence of the adversarial nature of Western democracy today.” The myth of authoritarian superiority is drawing its strength from a fundamental critique of democratic processes: “Endless political backbiting, bickering and policy reversals, which make the hallmarks of liberal democracy, have retarded economic and social progress and ignored the interests of most citizens.” More recently, Asian autocrats, according to the BTI 2022 regional report, “have readily and often invoked a comparison between the ‘successful’ crisis management pursued by China’s government and the ‘failure’ of Western democracies” in response to COVID-19.

For maybe too long a time, these critiques were shrugged off too casually by the democratic fold. Discrediting the institutional settings of democracy (and not just performance) as being inherently inefficient does strike a chord among disenchanted populaces. During the past few years, several heads of state undermined rule of law with the proclaimed and popular goal to achieve more state efficiency, like in Benin, El Salvador, the Philippines and Tunisia. Three problems arise for this storyline, however: First, the price paid in loss of democracy quality was high, and the alleged gains in efficiency and governance never materialized. Often, populist governments with authoritarian leanings simply established their own wasteful clientelist system. Second, key aspects of China’s economic success are particular to China. The country has a meritocratic promotion system and combines economic and administrative decentralization with a system of political centralization that is functional and secures loyalty. These aspects have nothing to do with the authoritarian government as such, and they also cannot simply be replicated in other countries. And third, the tale of autocratic superiority is disturbed by neighbours with a fair (Ukraine) or very good (Taiwan) governance record that offer a democratic alternative.

Autocratic governance scorecards revisited

Generally, there is a vast efficiency and steering capability gap between democracies and autocracies. Instead of being able to act swiftly and effectively in the sense of a propagated, well-functioning development dictatorship, the average autocratic policy coordination on the BTI’s 10-point-scale falls short of democracies (-1.69), the use of available resources is significantly less efficient (-1.85), and the discrepancy between autocratic and democratic anti-corruption policies is particularly large (-2.14). Steering capability in terms of prioritization, implementation and policy learning is also considerably weaker in autocracies (-1.91). In all output-related aspects, the gap is similar. As autocratic rulers have no democratic mandate and are thus even more dependent on deriving their legitimacy from their social and economic record, this is a devastating assessment. Truth is that for every well-governed autocracy like Singapore, there are ten other authoritarian governments that are highly corrupt, bankrupt, hugely inefficient and based on predatory clientelism. The myth of autocratic efficiency simply does not hold empirically.

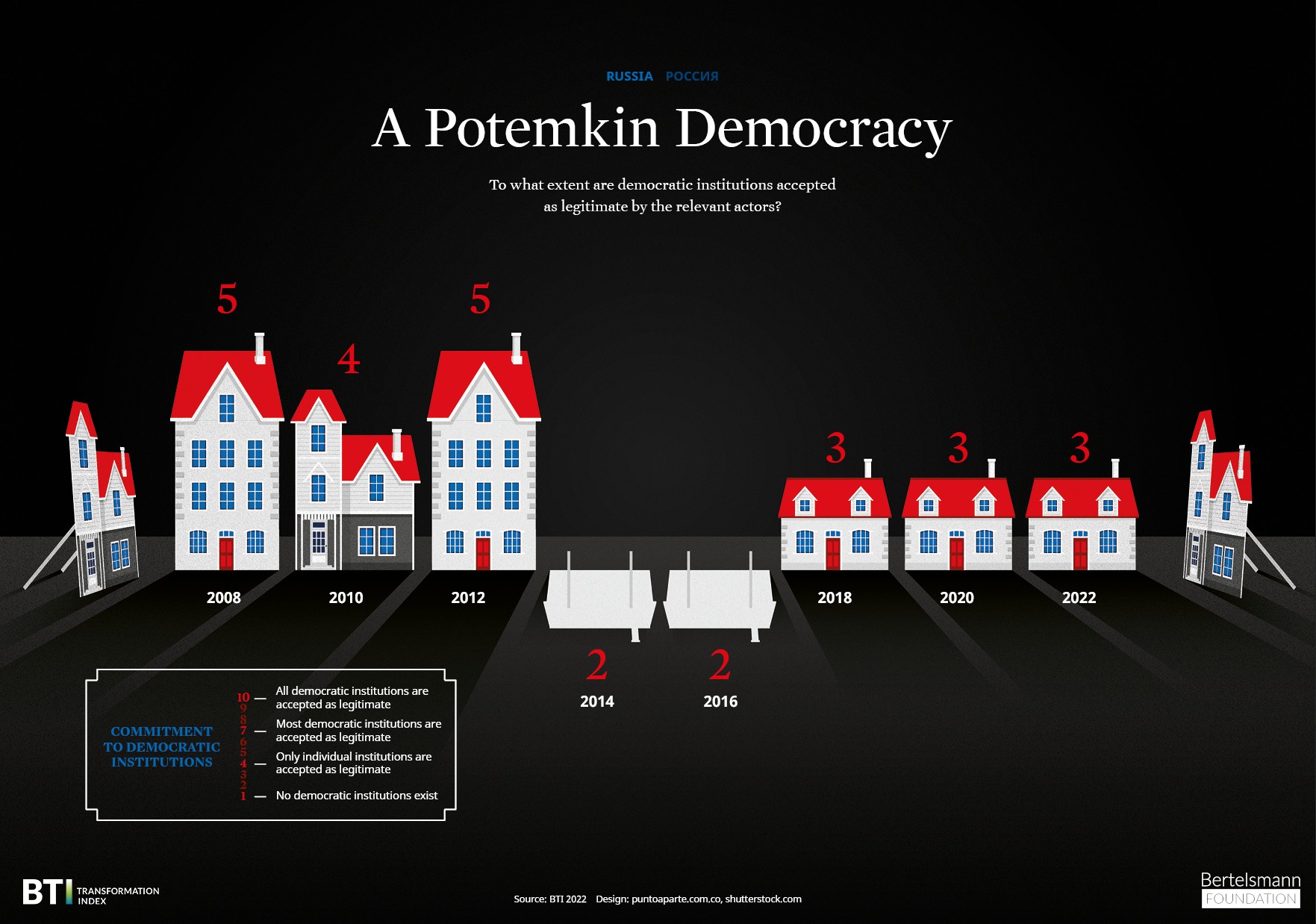

China and Russia do not fare well in governance, either. However, they play in decidedly different leagues. As Odd Arne Westad recently pointed out, “China is a communist state where the party rules in what is claimed to be a meritocratic manner on behalf of the people,” whereas “Russia is a personalized kleptocratic dictatorship that masquerades as a democracy.”

This difference reflects in governance scores, as published by the BTI 2022. China is well above global average in terms of steering capability and resource efficiency, with clear deficits in consensus-building and international cooperation. Russia, by contrast, is sub-par in all governance criteria, a wasteful, badly coordinated and unsuccessful regime whose legitimacy is wearing thin. While both regimes face a plethora of similar structural constraints, among them environmental degradation, regional disparities and demographic change, Russia meets considerably higher legitimacy challenges.

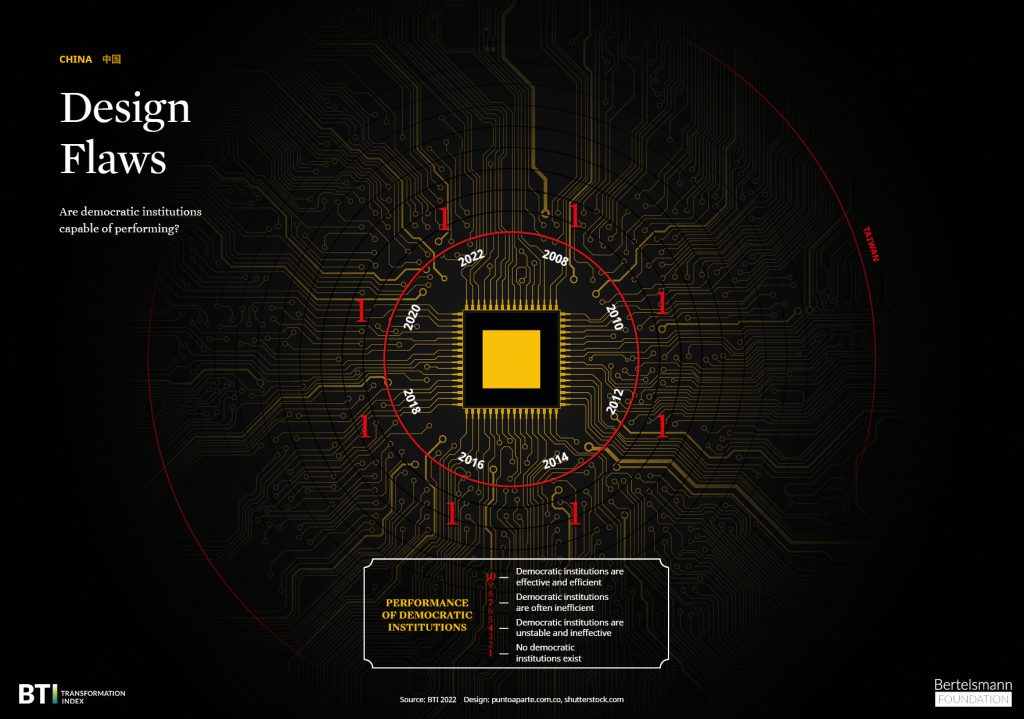

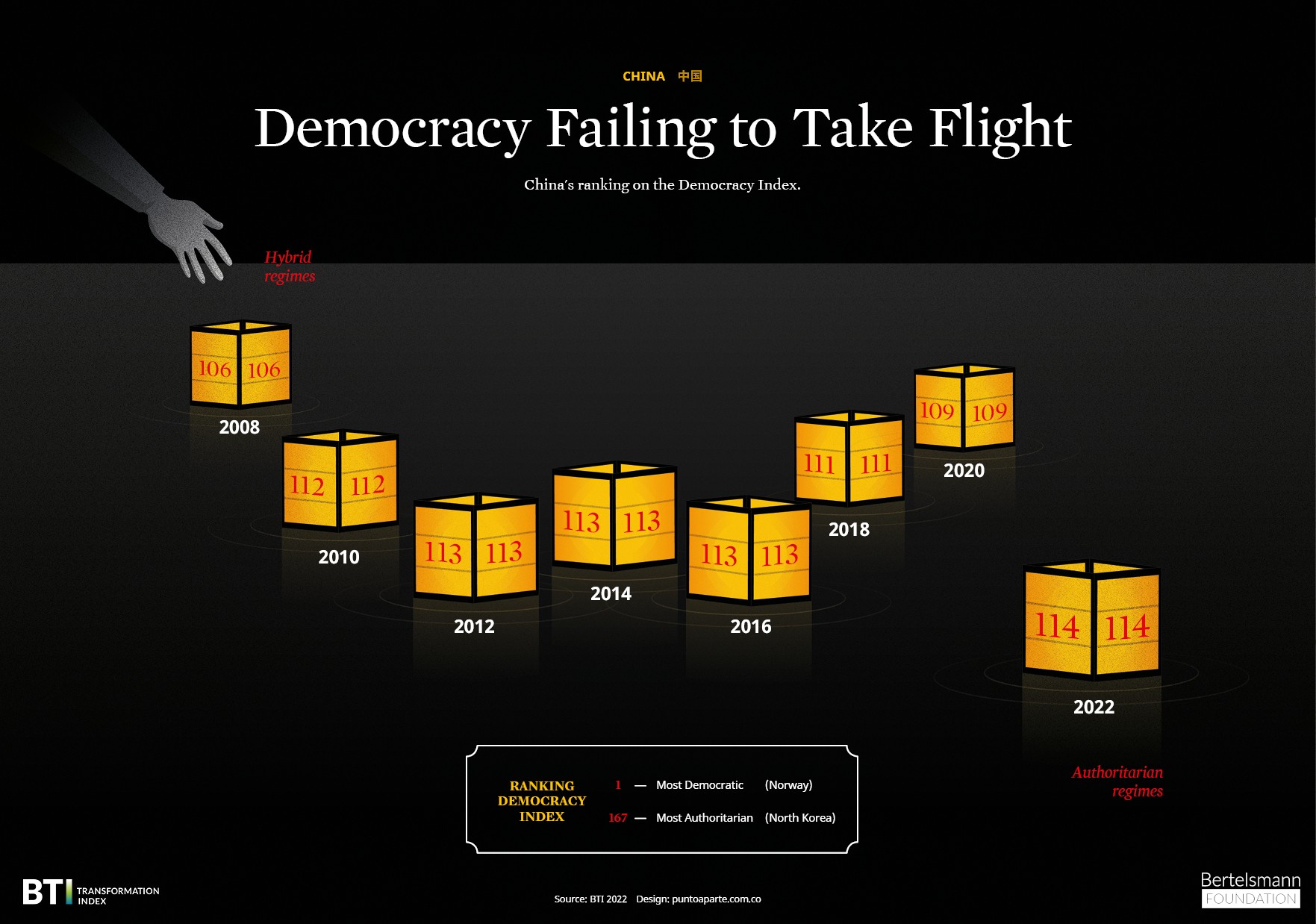

Autocratic regimes under pressure tend to heighten repression domestically and aggression internationally. The Russian government’s drastic curtailment of political participation rights led to a marked drop in political transformation of -0.95 points during the last ten years, but did not quell political protests. China has a very low political transformation status to begin with.

Ultimately, the Chinese centralization and personification of power will lead to losses in political learning capacities and cooperation abilities with the regional government levels. Increased surveillance and repression kept things stable, but this could possibly change when the cul-de-sac of a repressive Zero-Covid-strategy (or even a “flexible zero”) poses further challenges to the legitimacy of the ruling party.

International consequences

In international cooperation, China (-1.4 points) and Russia (-1.3 points) heavily lost in credibility and assumed a more aggressive posture. This now escalated into warfare, as Russia invaded Ukraine. The ruthless attack was not just an aggressive diversion away from domestic legitimacy problems, nor was it solely an imperialist reflex to reign into a perceived Western expansion into a self-defined cordon sanitaire. Most importantly, as Robert Person and Michael McFaul have explained, “the primary threat to Putin and his autocratic regime is democracy, not NATO.” A democratic and successful Ukraine would be a constant challenge to the narrative of superior autocratic governance.

By that token, “Taiwan’s successful democratic government is a similar thorn in the side of the regime in Beijing as a democratic Ukraine is to the regime in Moscow.” Ukraine, with all its democracy deficits and governance weaknesses, does represent a post-Soviet alternative to an autocratic Russian empire, just like Taiwan constitutes a democratic Chinese alternative, and a hugely successful one. In that sense, and in addition to solidarity and humanitarian considerations, much is at stake in Ukraine now. Beijing will carefully note the reaction of democratic governments in response to this extreme violation of international law and human rights. If Moscow’s aggression ultimately fails, resulting in a further loss of legitimacy or possibly even regime change, Beijing will think twice before also entering such hazardous adventurism. But if the community of democracies misses the chance for a united, unequivocal and steadfast response, the Chinese leadership will assume greater leeway for aggression toward Taiwan. The price the Russian regime has to pay needs to be high, also to avoid just that.

This article first appeared on April 25, 2022 in the blog of the China Institute at SOAS, University of London: Democratic neighbours as a challenge to the autocratic superiority tale. A heartfelt thanks to Aki Elborzi and his colleagues for an excellent collaboration.

The illustrations were taken from the fourth volume of Graphic images, a series produced by the supercreative brainpool modestly dubbed as Bertelsmann Foundation of North America. A very special thanks to our Washington colleagues for their outstanding illustrations of BTI data.