Africa’s Agenda 2063: A Long-Term Vision with a Long Road Ahead

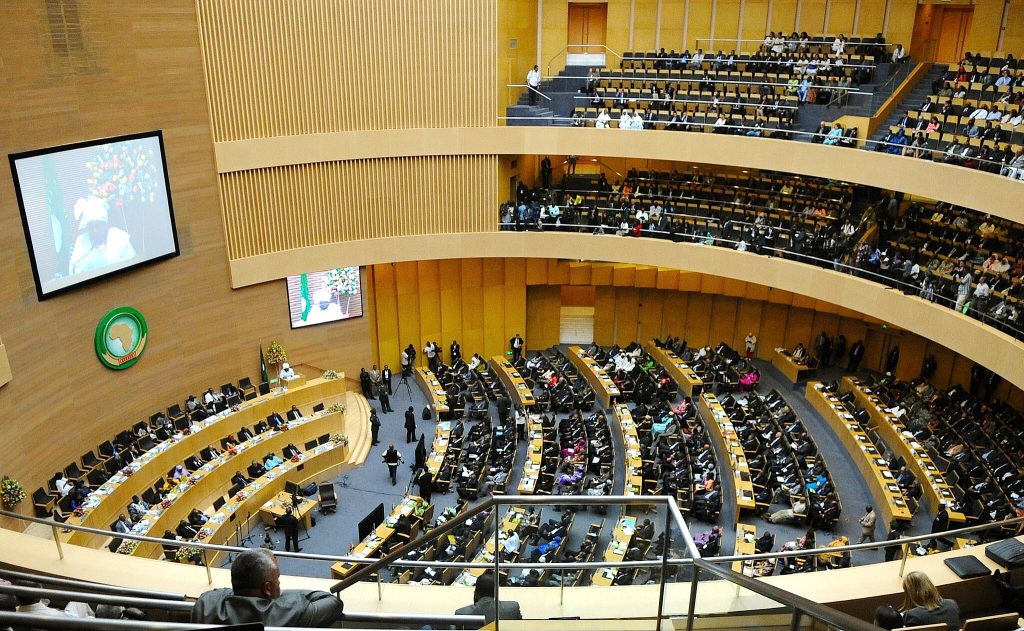

With Agenda 2063, the recent African Union (AU) summit in Addis Ababa focused on a plan that outlines the vision of a fully integrated, prosperous, and peaceful Africa. However, cooperation among individual states, which is necessary for this vision, is in poor shape for various reasons – despite examples of successful collaboration.

At its founding in 1963, the Organization of African Unity (OAU) formulated the key to a free and flourishing Africa, which was reflected in its name. The heads of state and government were aware that this goal could only be achieved if the continent were united and if governments collectively embraced the principles of responsible governance.

The African Union (AU) deliberately chose a target year for its Agenda 2063 that alludes to the vision of its predecessor organization. This strategy for Africa’s transformation includes five ten-year implementation phases. The first ten-year plan (2013–2023) focused mainly on economic growth, integration, governance, and peace. Key initiatives included the Single African Air Transport Market (SAATM) and the Silencing the Guns initiative. According to the Continental Report on the Implementation of Agenda 2063, some progress has been made, such as with the flagship project African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which has been signed by 54 member states. The second ten-year plan (2024–2033) aims to accelerate progress and strengthen implementation. However, the fact that the AU imagines its goal of a united, integrated Africa will be achieved several decades in the future indicates the continent still has a long road to travel.

Fragile Progress

It is clear that the continent has surged forward in various areas, as some of the world’s fastest growing economies are in Africa. ICT innovation hubs are thriving, more people are receiving education, better health services have been implemented, and infrastructure has improved in many areas, including the emerging Standard Gauge Railway network, which will connect Kenya, Uganda, South Sudan, the DR Congo, Rwanda, and Burundi.

While there is reasonable hope of good governance and democratization going hand in hand with active societies, there are concerns that progress is fragile. A brief look at the continent immediately reveals political instabilities, a decline in freedoms, and setbacks in democracy. Poor governance thrives, with institutions plagued by corruption, ethnic divisions, and general mismanagement. According to the BTI Transformation Index, many African countries perform weakly in the governance dimension.

The coexistence of progress and stagnation is particularly evident in countries the Governance Index classifies as moderate, such as Kenya. Promising developments under President William Ruto in the areas of rule of law, economic growth and climate policy, which are also visualized in the BTI Atlas, are offset by rampant corruption and high national debt. In 2024 the country was further tested by violent youth protests, which culminated in the storming of the parliament.

Many people on the continent still yearn for administrations that can better manage resources, conduct affairs in a transparent manner, and uphold human rights. So, can regional integration serve as a tool for better governance in Africa, a continent of 1.4 billion people in 54 countries?

Approaches to Successful Integration

The Agenda 2063 captures the aspiration for a fully integrated continent by focusing on economic cooperation (such as the Single African Air Transport Market (SAATM)), the promotion of democratic governance, and resolving conflicts. The final aspect of integration is the establishment and strengthening of continental institutions. One of the practical benefits of an integrated Africa is an environment where people can move freely across borders, bringing with them knowledge, goods, and services.

There are good examples of integration on the continent. The East African Community (EAC) has achieved some success in integrating countries such as Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, South Sudan, Rwanda, Burundi, the DR Kongo, and more recently, Somalia. Institutions, including the East African Legislative Assembly, a common customs union, and a common market, have evolved. The countries also usually find a common voice on continental and international matters.

Furthermore, the EAC allows free movement of people, goods, services, labour, and capital among its members. To ensure peace and security in the region, the community has set up conflict resolution mechanisms.

Particular Interests and Powerless Institutions

On paper, the African Union has clearly articulated its aim to expand such approaches for successful integration, and its leaders often speak about the need for an environment where people can move freely across borders, thus accelerating integration.

Yet the process has been slow, if not stagnant, as African governments have limited interest in further integration. One reason for this is that many countries are focused on their own internal political, economic, and social challenges, overlooking the bigger picture.

It is evident that these governments have not developed effective agreements or harmonized legislation to facilitate free movement or integration. At the same time, there are frequent border disputes, which further challenge the movement of people, goods, and services. In many cases, security checkpoints and roadblocks can be encountered both at national borders and within countries themselves. Wars and political instability often disrupt existing arrangements as well.

Whereas AU member states have often agreed on protocols, regulations, and directives, their governments have been sluggish in adopting these decisions for implementation or do not implement them at all. There is also a form of protectionism, in which member states want to keep their independence.

One example is the AU Protocol on Free Movement, adopted in 2018 by the African Union. It was meant to allow citizens of member states to move and work freely across borders, but it has not been ratified or implemented by many countries. One such country is South Africa, where the government emphasizes the need to meet certain prerequisites before implementing free movement, including strengthening integrated border management. Other states are concerned that open borders could place greater strain on their labour markets and social systems.

Meanwhile, the AU bodies are poorly funded as they rely on contributions from member states, which are often delayed or unpaid, leaving the institutions in severe financial distress. The AU receives financial assistance from international donors such as the EU, the UN, and non-governmental organizations and foundations, but that assistance has faced challenges due to ongoing global economic problems. To foster successful integration and improve governance, the AU must ensure adequate funding for its institutions. After all, in recent years, the AU has tried to strengthen its financial autonomy – for example, by introducing a 0.2% levy on imports in member states to increase self-financing.

Substantial Progress is Needed

Another key obstacle to realizing the vision of successful integration lies in the structural constitution of the AU. Although it includes institutions such as the AU Commission, the Pan-African Parliament, and the African Court of Human and Peoples’ Rights, authority is vested in the assembly, the gathering of heads of state. Thus far, they have refused to delegate authority to the AU’s organs. As a result, the Pan-African Parliament does not exercise binding legislative powers.

To implement the AU’s vision of a united and prosperous Africa, member states must be urged not to cling to their self-interest but to work towards effective agreements or legislative harmonization to facilitate the movement of people, goods, and services. Furthermore, the African Union must work harder to end wars, conflicts, and disputes among its members. To this end, it would be helpful if the African Union had greater capacities for peacekeeping – for example, in the form of peacekeeping troops modeled after the UN Blue Helmets. Without overcoming selfishness and implementing more effective structures, the vision outlined in Agenda 2063 will remain a distant future goal.

A version of this article is published by the Fair Observer