Hiring Bullies as Bouncers

Facing record immigration numbers, the European Union has started to look into closer cooperation with governments in Africa. In the Khartoum Process, the EU intends to set the fox to keep the geese, as it is those governments’ actions that people are trying to run away from.

This article is part of our “Migration & Transformation” series. Many governments and civil societies in developing and transition countries are confronted with the influx of larger numbers of displaced people. BTI experts and journalists investigate the political, economic and social challenges facing host countries such as Kenya, Lebanon, Pakistan, South Africa and Turkey. The authors identify problems and problem-solving strategies on the ground and assess multilateral responses.

As 1,014,836 refugees and irregular migrants crossed the Mediterranean Sea in 2015 on their way to Europe and another 3,771 were counted dead or missing by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the European Union and its member states have increasingly struggled to bring their moral and legal obligations into harmony. On the one hand, people in need deserve shelter; on the other hand, borders must be protected against unwanted immigration.

Decision-makers operate in an increasingly nationalist atmosphere, mutually stoked by populist politicians and citizen movements that mobilize against immigration and diversity. Consequently, even core achievements of the European integration process, such as removing border controls within the Schengen area, have come under serious pressure. To the outside world, the EU is expected to act as a unified bloc in order to combat irregular immigration. Border protection around the EU has been boosted through the specialized agency Frontex, and the EU has concluded various readmission agreements and mobility partnerships with partner governments. Finally, individual cooperation activities have been initiated, such as training programs for border guards and security forces in neighboring countries like Tunisia and Egypt.

Increasing Cooperation With Africa

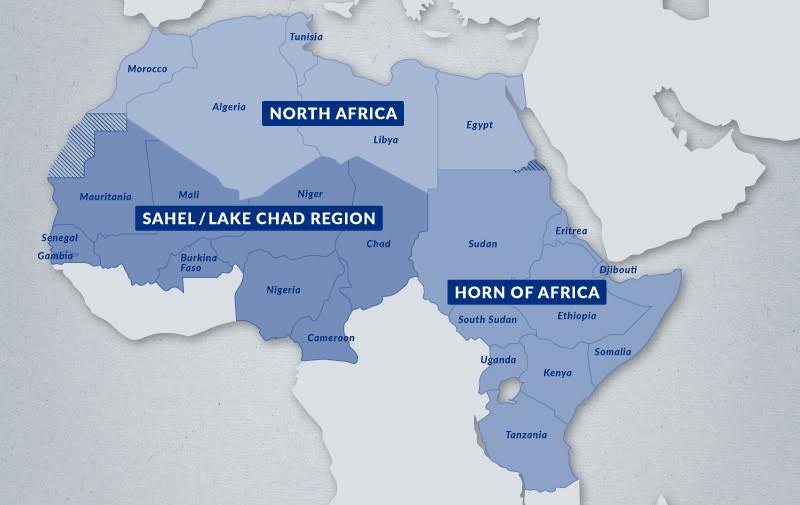

For years, cooperation with Africa has been one of the EU’s prime concerns in securing its borders. The Rabat Process, concluded in 2006 with 28 countries from North, West and Central Africa, was the first structured regional cooperation aimed at tackling irregular migration on the Western Africa route. It was accompanied by the Migration, Mobility and Employment Partnership, which the EU concluded with the African Union in 2007. In one of the latest initiatives, the EU invited the governments “around Sudan” to the Khartoum Process in November 2014, officially called the “EU–Horn of Africa Migration Route Initiative,” to tackle irregular migration on the Eastern Africa route as well.

A meeting of the initiative’s steering committee in the Egyptian city of Sharm El Sheikh in April 2015 brought some initial ideas to light. Besides many ideas to strengthen the local economy and job prospects for young people, the final document, leaked by Statewatch, contains stipulations like “Strengthening the Human and Institutional Capacity of the Government of state of Eritrea in the fight against human trafficking and smuggling,” “improving border management capacity” with the government of South Sudan, and a “Training Centre for the … Khartoum Process Countries at the Police Academy in Cairo.”

The Valletta Summit in November 2015, where representatives from the EU and its member states discussed migration issues with state officials from Rabat and Khartoum Process countries, brought an EU Emergency Trust Fund and another action plan into being. For the trust fund, 1.8 billion euros ($2 billion) have been earmarked over five years for projects to support local initiatives.

How exactly this will be done remains to be seen. For the moment, all that is clear is that the countries participating in the Valletta Summit Action Plan will be divided into three regions.

All projects will be managed by the EU delegations in the respective countries, which can expect quite different amounts of fiscal support. For the five countries in the North Africa region, the initial part of the budget is not supposed to exceed 200 million euros ($222 million), or an average of 40 million euros ($44 million) each. The remaining 18 countries can expect an average of about 88 million euros ($98 million) each, yet with significant differences based on each country’s size and needs.

Policies and Performance of Partner Governments

The approach the EU has chosen is highly questionable. Given the overall performance of most governments involved and, in particular, their human rights records, one can only conclude that the EU has decided to hire bullies as its bouncers. A look at the data of the latest Bertelsmann Transformation Index, BTI 2016, reveals the considerable shortcomings of these states. In the Political Status Index, which analyzes where countries stand on their path towards democracy under the rule of law, most of the nations involved are at the bottom third of the list: Somalia comes last at 129, Eritrea at 127, Libya at 126, Sudan at 125, Ethiopia at 113, South Sudan at 111, Chad at 104, Morocco at 93, and Egypt at 91.

These countries still show major shortcomings in protecting citizens’ basic rights. The BTI 2016 country reports speak of state authorities’ extensive disregard for the rule of law, including random arrests of citizens, torture and mistreatment of prisoners, and systematic violations of civil rights. Forced labor and organized slavery remain widespread phenomena, particularly among refugees and irregular migrants who enjoy less legal protection than local citizens and who are often abused by local smugglers and criminal gangs. The situation is even worse in territories without sufficient governmental control, such as wide parts of Libya and Somalia, but also in the northern areas of Nigeria controlled by Boko Haram.

The EU and its member states are of course very much aware of this. Yet they still push for cooperation with these governments, announcing greater support for local citizens and protection of local refugees. In reality, however, they know perfectly well that all these measures will absolutely not help improve the situation for particularly vulnerable people like refugees. The refugees will remain stuck somewhere between the Horn of Africa and Africa’s northern coastline, and when the situation becomes unbearable, they will board a boat due to the lack of alternative options. The EU is willing to pay a lot of money to regimes that will only strengthen their illegitimate power structures and continue blackmailing Europe in the future: if you want us to keep our borders closed, you have to pay more. Turkey is an illustrative example, with its deteriorating democratic qualities, the restructuring of its state and society, and its blatant disregard of basic human rights. EU representatives keep quiet about all this for the sake of better border control, and will not put pressure on President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to change for the better.

The same can already be seen in North Africa. Egypt’s blatant policy failures and human rights violations may lead to a condemnation from the European Parliament—but this will not have any impact on real politics. France is happy to export its weapons, Germany is happy to sell its engineering expertise, and Italy is happy to explore the country’s gas fields. And all of them are happy to have Egypt stable, even if stability is only a façade.

Europe wants to have the refugees and immigrants out of its consciousness. Sadly, the suffering of millions is not Europe’s business as long as they don’t make it into the headlines. Against the surge of populism, racism, and radicalism back home, this is exactly what European decision-makers want, and to achieve this, they even sign pacts with governments whose respect for human rights and human dignity is anything but sufficient.

So, what needs to be done? The often-heard slogan, that one should improve the living conditions back home so that people are not forced to leave home anymore, is certainly correct, though there is no simple recipe to achieve it. The situation in Somalia, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Sudan, Egypt, and all other countries will not improve in the foreseeable future. So, instead of wasting money on cooperation programs that bear doubtful results at best, it would be better to use the same money to establish secure ways into Europe. Let people fly into Paris, London, Frankfurt, and Amsterdam, and fund sufficient registration facilities in these cities in order to correctly process asylum claims and requests. Refugees then could make it to Europe for an average price of less than 400 euros ($450) from Addis Ababa or Cairo to Europe, instead of paying bribes and exaggerated sums of several thousand dollars to smugglers and traffickers.

The EU directive 2001/51/EC prevents governments from making this policy change, as air carriers have to make sure that only those with a valid visa will be allowed to board a plane to Europe. Its revision would be a first step in reducing fatal incidents in the Mediterranean. It does not look as though this will happen, but the EU, or more precisely the governments of its member states, are still responsible for the hundreds of thousands that remain stuck in North African prisons; are abused, raped, and sold by criminal gangs; and drown during their final attempts to reach Europe.

I agree with your recommendations, and there is a lot of things that can be done to accommodate that number of refugees, for example by specifying a dozen European airports to receive refugee applications (or 1 airport per EU member state) where refugees can fly to directly and register. There are many solutions that can save lives and also prevent a migrant crisis in EU.

Dear M Elkhateeb, thanks a lot for your positive feedback, I appreciate your efforts and support!