The Albatross around the ANC’s Neck

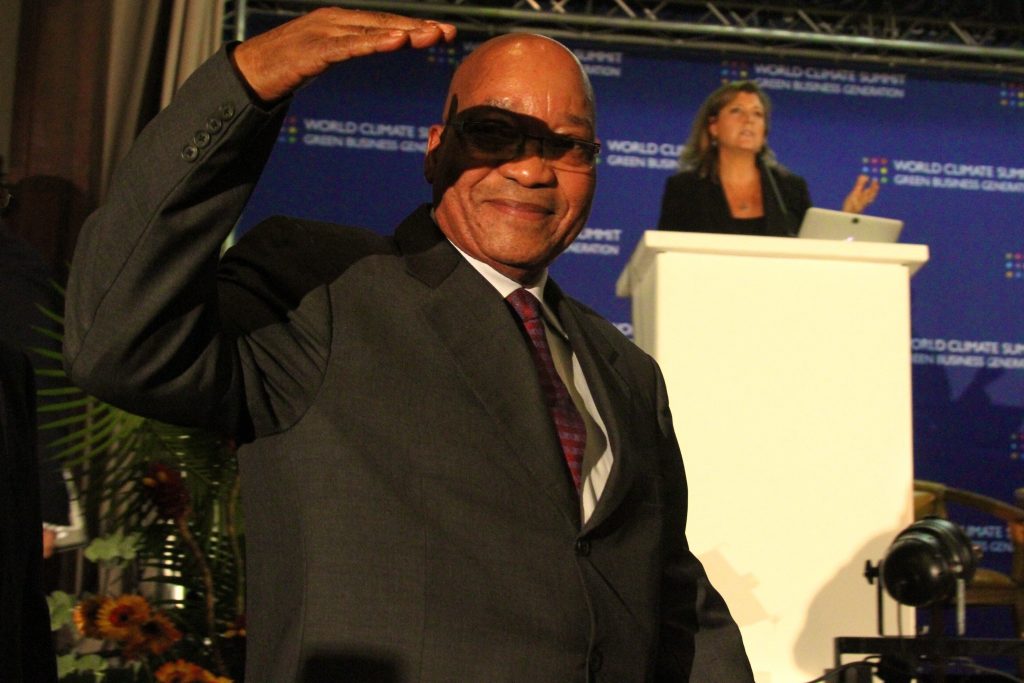

Last summer, President Jacob Zuma was celebrating his narrow success of surviving another no-confidence vote. But while the ANC’s 54th National Elective Conference is approaching, many within the governing party are beginning to count the cost of a leader who lacks the public’s trust.

In December 2007, delegates at the National Elective Conference of South Africa’s ruling African National Congress (ANC) took an ill-fated gamble on the party’s future. So deep was the resentment of the technocratic impulses of its former president, Thabo Mbeki, that the world’s oldest liberation movement, once led by icons like Nelson Mandela, lost its senses and elected to power, Jacob Zuma, a highly compromised character, who at that time stood trial on 783 corruption charges and shortly before had been acquitted on rape charges, after admitting to have had sexual intercourse with the daughter of a close friend.

This decision, which the ANC leadership at the time hailed as a product of the organization’s “collective wisdom”, has become its collective nightmare. Once in office, Zuma proceeded to leverage the ANC’s cadre deployment policy and a powerful presidency, bequeathed by the Mbeki administration, to entrench an intricate patronage network throughout party and state, aimed at enriching his family and sustaining those dependent on his incumbency. Zuma never managed – nor made any serious effort – to shake off the controversy that dogged him before his ascension to the country’s highest office. For most of his term in office, it was never necessary to do so. As power shifted within the party in the wake of the 2007 elective conference, so it did within state where Zuma allies took up key positions within the prosecuting authorities and intelligence agencies.

Poor governance and corruption

While several of his patronage deployments have been turned down by the courts for being either underqualified or unsuitable for their respective positions, many other weak appointees made their way into the governance system, resulting in the hollowing out of capacity and the erosion of good governance practices in key government departments, law enforcement agencies, and state-owned enterprises (SOEs). As a consequence the latest BTI 2016 South Africa Country Report of the Bertelsmann Foundation pointed to growing public anger with “the proliferation of corruption and incompetence at various levels of government”. In the Foundation’s most recent Transformation Index (BTI), the country’s overall score for democracy declined from 8.70 in 2006 to 7.60 in 2016. Not surprisingly, when S&P Global and Fitch, two of the three major global ratings agencies, downgraded the sovereign, along with key SOEs, to junk status earlier this year, both singled out policy uncertainty as the major contributing factor to their decision.

As the ANC prepares to elect Zuma’s successor in December this year – although not incorporated in the party’s constitution, the practice of a two term presidency is entrenched – many within the party, including some of his most vocal erstwhile supporters, are counting the cost of a toxic, predatory presidency that was unleashed upon the state. Amid conditions of anemic growth and the highest unemployment levels in a decade, the consequences of his mismanagement are increasingly widening the gap between reality and the party’s slogan of “a better life for all”.

Zuma’s approval rates at an all-time low

Not only will the next ANC leader inherit a morally compromised and deeply divided party – recently up to 35 ANC members voted in favor of a parliamentary no-confidence vote against Zuma – but there is for the first time no certainty that the organization’s next chairman or chairwoman will return to the Union Buildings in Pretoria as the country’s head of the state after the 2019 general elections. In the 2016 local government elections the party ceded control of the country’s economic hub, Johannesburg, the administrative capital, Pretoria, and Nelson Mandela Bay, the largest metropolitan area in the home province of former president, Nelson Mandela. Overall, ANC support dropped to 54% from the 66% that it recorded two years earlier during the 2014 general elections. The reasons for this decline all point in one direction. In the 2015 round of the Afrobarometer survey, only 34% of respondents indicated trust in the office of the president – the lowest ranking for any ANC leader since the country’s political transition almost a quarter of a century ago. In a more recent poll by the 24-hour news station, eNCA, in May this year, 62% of ANC voters disapproved of Zuma’s leadership.

But also on other fronts the tide has started to turn against Zuma. In March 2016, the country’s Constitutional Court found him to be in violation of his constitutional obligations in a matter relating to the use of government funds for the upgrading of his private residence. In May the same year, the Pretoria High Court ordered the reinstatement of the 783 corruption charges that were controversially dropped by the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) shortly after he assumed office, and a month later, a damning report by the country’s public protector ordered a judicial inquiry into alleged improper influence by the Gupta family – three politically-connected brothers, with close ties to the president – not only in the awarding of government contracts, but even the hiring and firing of government ministers. Importantly, it also asked pertinent questions about the extent to which Zuma may have compromised the integrity of his office through his relationship with the Gupta family, which also happened to employ his son. In 2017, the cost of his incumbency continued to exert its toll on the ANC as the systematic release of leaked email correspondence between Gupta associates gave further credence to existing allegations about their involvement in the capture of key state institutions, and more court appearances are scheduled in relation to his reinstated corruption charges.

Potential successors for President Zuma

None of this bode well for ANC attempts to revive the party’s fortunes before 2019. To do so, it will have to distance itself from Zuma and his legacy. Yet, driven by a profound fear of being prosecuted by a hostile candidate, Zuma is now in survival mode, and backed by a deeply entrenched and fiercely loyal patronage network that has much to lose from his departure, the president will be pushing hard for his chosen candidate, his ex-wife and former African Union Chairperson, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, to succeed him. For the same reason, his faction will also be pulling out all stops to put obstacles in the way of Dlamini-Zuma’s main contender, deputy president Cyril Ramaphosa.

For many disillusioned South Africans, who have witnessed economic decline and a drop in governance standards under the Zuma administration, the election of Dlamini-Zuma will mean only one thing – more of the same. And more of the same will mean that the party will ultimately be dragged down below the 50% threshold in two years’ time. Given Zuma’s own prediction several years ago that the ANC will rule until Jesus Christ returns, the second coming may indeed be upon us.

Jan Hofmeyr is the Head of Research and Policy at the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation, Cape Town, South Africa. He writes in his private capacity. Hofmeyr is one of 246 country experts who worked on the latest edition of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index, BTI 2016.