World Cup 2018 Confirms: Democracies Better at Playing Football

One of the many rituals of a football World Cup is to take comprehensive stock after the tournament. So it’s time to review our Democracy World Cup and analyze our predictions. Were we right in our thesis that there is a connection between a country’s democratic quality and the performance of its national football team?

Historically, the question can be answered relatively clearly: in the 18 World Cups since the end of World War II, democratically governed countries have won the title 16 times (the 2 exceptions were Brazil in 1970 and Argentina in 1978, both then under military rule). For this year’s democracy test, we compared the 32 participating nations in five key areas of democratic quality on the basis of the independent assessments of the Bertelsmann Stiftung democracy indices – the Transformation Index (BTI) and the Sustainable Governance Indicators (SGI). We have compiled the essential takeaways on each country in one-page profiles. Our predictions for the matches resulted from the direct comparison of the two opponents along the five categories based on the assumption that the team whose country is ahead in terms of free elections, freedom of speech, protection of civil rights, social inclusion and the fight against corruption will also prevail in the game.

The result: in 30 of the 64 matches we predicted the actual winner with this system. With a hit rate of 48 percent, we beat most animal oracles who regularly appear during World Championships and can compete with many of the prediction methods based purely on sports-related data. But betting your savings along our forecast would not have been advisable overall as our predictions were not sufficiently precise.

This was primarily due to the fact that we were more often out of line in encounters between democracies. The more closely our assessments of democratic qualities between the opponents, the less reliable our ability to forecast. If democracy quality alone would decide a game, then Sweden, Denmark or Iceland would have stayed in the tournament much longer. Germany would not have been eliminated in the preliminary round either.

Our forecasts were most reliable in games of opponents at low or very different levels of democracy. As soon as at least one of the 5 qualified autocracies was involved, our model matched the outcome of the game in 69 percent of the cases; we correctly predicted 9 winners of the total of 13 matches. In all Group A matches with democratic Uruguay and the autocratic regimes of Egypt, Russia and Saudi Arabia, the democracy comparison between opponents matched the winner of the match. With that odds, you can be way ahead in any betting pool.

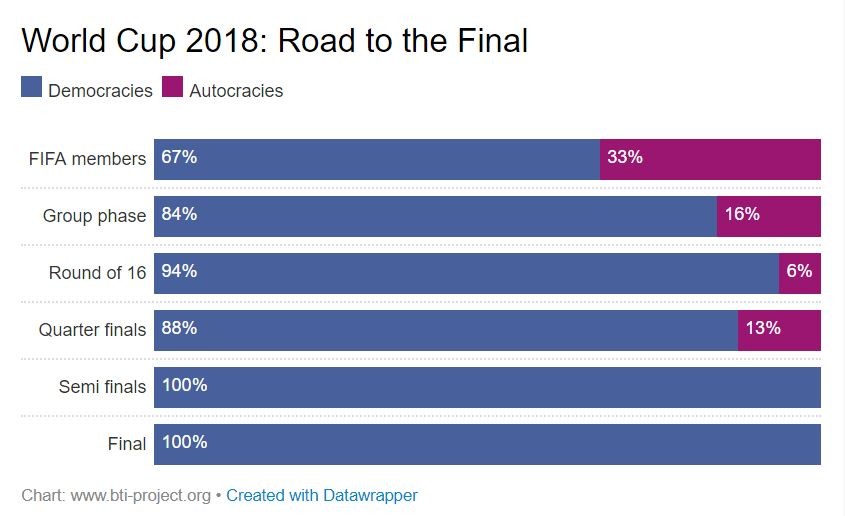

The overall course of the 2018 World Cup, including the qualification phase, also shows that democracy and football may have more to in common than generally assumed: The ratio between FIFA-organized football associations from democratic and autocratic states is 2:1. More than five times as many democracies as autocracies qualified for the 2018 World Cup. After the group stage the ratio was 15:1 – host Russia was the only autocracy left in the tournament.

Are there explanations that democratically governed football nations do better than autocracies, which go beyond coincidences? The British magazine Economist also tried to define influencing factors beyond the football pitch in the run-up to the World Cup. The result: Prosperity, the size of the country and the popular enthusiasm for football can explain up to 50 percent of the national teams’ performance in international comparison. The rest, at least in part, is determined by the extent to which countries rely on creativity and individual decision-making competence when training their young players or how open they are to international influences – both in naming their own squad and in deploying their players in the world’s best leagues.

Football, as many of the stock-taking articles of the World Cup 2018 show, always serves as a projection screen for all kinds of social and political developments. Is Germany’s group stage exit a reflection of the government coalition’s lack of team spirit or even the crumbling social cohesion of German society? Will France’s title win boost President Macron’s underground approval ratings similar to 1998? Shouldn’t Europe also draw political confidence from the fact that for the fifth time in the history of the World Cup, the semi-finals were fought out exclusively between teams from the Old Continent? And did the football festival in Russia only contribute to legitimizing Putin’s authoritarian style of government or also help to break up old stereotypes and images of enemies among hosts and visitors, which does not change Russian politics overnight, but perhaps the acceptance of authoritarian structures among the population?

Football remains the most beautiful side-issue in the world and we should not overload it with too many projections and supposedly reliable forecasts. Our aim was to draw attention to the conditions next to the pitch from time to time, while enjoying the game. We enjoyed the experiment. It has given us food for thought for our own work. It has given us new food for thought for our own work. Although we have not yet fully embraced the location and time of the 2022 Winter World Cup, we are ready to start the next test in four years’ time. Hopefully with such excellent partners as the blog 120 Minuten and the Argentinean think tank CADAL.

There is no final certainty as to what sports-related or non-sports-related factors need to come together to win the title. Fortunately, this World Cup has once again proved how wonderful and unpredictable some of the matches are. In sporting terms, Jogi Löw will hopefully be able to successfully analyze the early elimination of the German national team. However, one conclusion of our somewhat different #DemocracyWorldCup is – so far at least – not yet refuted: Democracies are simply better at playing football!