Indonesia as a Pillar in the EU’s “Pivot to Asia”

The EU’s external relations are in turmoil. In the West, the United States has shaken the once reliable and stable transatlantic partnership to the ground. In the East, China is rising as a strong and self-confident power with political and economic interests that are not always in line with those of the EU. In these difficult times, the EU needs partners beyond its traditional external networks. Especially it should diversify its approach towards Asia – the world’s prospective growth region in the 21st century. Indonesia could be a strong pillar of the EU’s “pivot to Asia”.

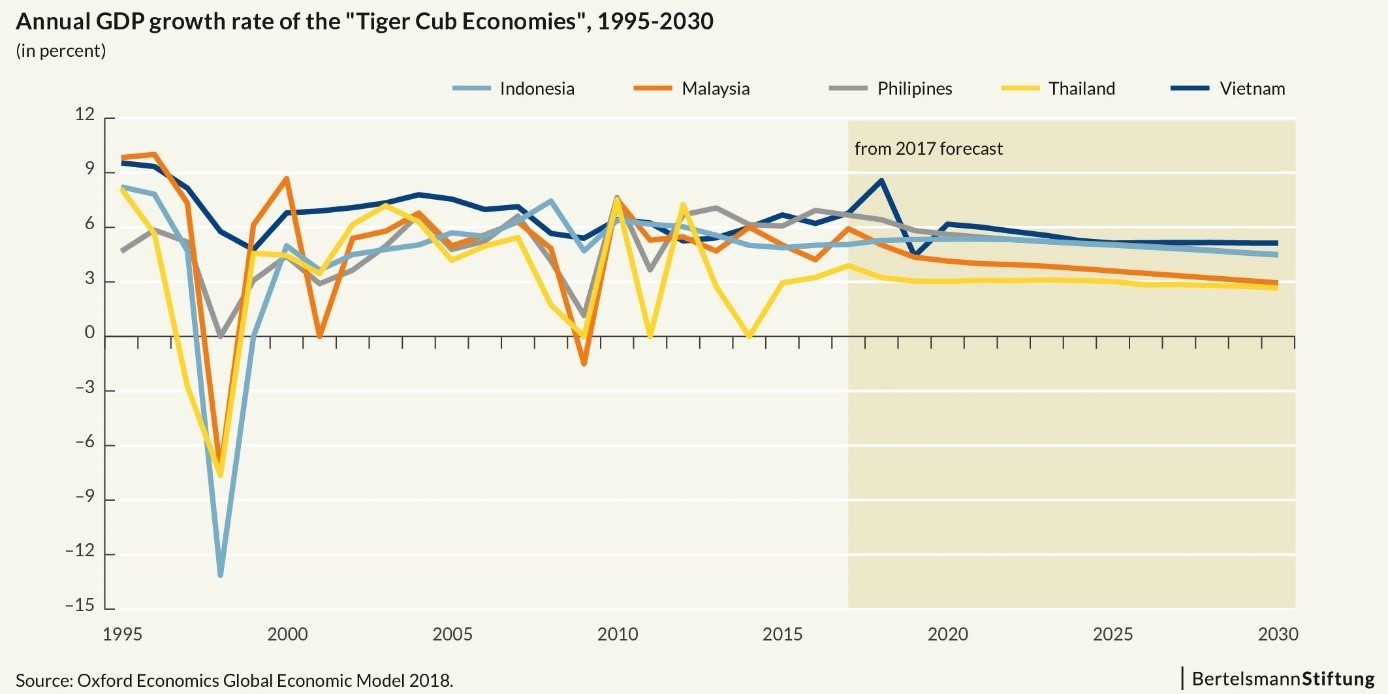

After the rise of the four Asian tigers (Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan) during the late 1980s and early 1990s, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam came to be known as the next generation of tiger states. They were even referred to as the “tiger cub economies” to express the high expectations associated with their economic potential. However, the Asian financial crisis of 1997/1998 destroyed this image even more quickly than it appeared, as the five countries experienced a sharp economic breakdown and struggled hard to get back on their feet. Meanwhile, China took over and became the dominating economic power in Asia and also in EU-Asian economic relations.

This also led to the way we talk about Asia in the EU, we more often than not mean China only. However, there is obviously more to Asia than China. And in the long run, growth in Asia will shift towards the South East of the region. According to the projections of Oxford Economics, Indonesia and the Philippines can still expect growth rates of around 4.5 percent, Vietnam even slightly above 5 percent in 2030. In contrast, China’s economic growth through 2030 could decline to an annual rate of two percent.

Free trade agreements (FTAs) between the EU and South East Asian countries have been one of the foci in EU trade policy: the FTAs with Vietnam and Singapore are formally concluded and currently undergoing next steps; negotiations with the Philippines, Malaysia and Thailand have been launched, however, with little or no progress (the latter two currently are on hold); negotiations with Indonesia finally started in the summer 2016 and are still on-going. The fourth round took place in February 2018 and according to the corresponding report “led to progress in certain positions and a better mutual understanding of respective positions”.

So before the next round of negotiations begins, which is supposed to happen later this summer, it is a good time for us to turn our attention towards the world’s 4th most populous economy and its economic relations with the EU.

Indonesia in international trade and investment

In terms of its share in world population and GDP, Indonesia already is the biggest among the tiger cub economies, ranking 4th and 16th, respectively. In terms of international trade and investment, though, Indonesia still is a dwarf. The country’s share in world exports was about 0.9 percent in 2016, in world imports around 0.8 percent. All tiger cub economies, except the Philippines, trade more with the world.

The situation is similar in regards to foreign direct investment (FDI). Indonesia currently holds about 0.9 percent of the world’s inward FDI stock. Its share in outward stock is even lower, amounting to 0.2 percent. Among the tiger cub economies, however, Indonesia has accumulated the highest inward FDI and ranks third in regard to its outward FDI stock.

Indonesia’s position in world trade is not unusual for countries with a large domestic market, which tend to have less incentive to open up to the world than small economies do. Annual growth rates of Indonesia’s foreign trade, however, have been stagnating in recent years. This is not surprising, since according to the BTI Country Report “[i]n the area of opening trade and investment access to its market, Indonesia has sent conflicting signals.” The government has recently eased restrictions in some sectors, while at the same time implementing stricter controls in others. So currently there seems to be no comprehensive commitment to opening up the economy.

Indonesia remains a difficult destination for foreign traders and investors. The World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business (EDB) Index and the OECD’s FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness (FDI RR) Index show this very well: The EDB Index ranks Indonesia 72 out of 190 countries. Among the tiger cub economies, only the Philippines with a rank 113 score ranks lower in regard to its business environment. In the FDI RR Index, Indonesia is among the top-10 of countries with the most hurdles for foreign investors, once more outranked only by the Philippines.

The state of liberalization of foreign trade and investment in Indonesia shows that the country would have the potential to increase its participation in the global economy, if this step was politically desired and became a strong focus of policy-makers.

Unharnessed potential: Trade and investment relations between the EU and Indonesia

Asia plays a key role in so-called extra-EU trade, that is, exchange of goods between the EU and the rest of the world. In 2016, the region’s share was already over 40 percent. China alone accounted for more than one third of this (14.9 percent), ranking first in extra-EU imports and second (after the United States) in extra-EU exports.

In contrast, the tiger cub economies only play a minor role in the EU’s trade with Asia. They have barely exceeded 1 percent of extra-EU trade in the last decade. Only Vietnam was able to achieve more dynamic growth in its trade with the EU, albeit starting from the lowest level among the tiger cubs.

Indonesia has been stagnating at 0.7 percent of extra-EU trade for more than a decade now, making it 29th of the EU’s trading partners. Both regions traded merely 25 million USD in 2016. For Indonesia, the EU is the 4th most important destination for exports and the 5th most important origin of imports. The apparent asymmetry in importance is of course due to the fact that the EU is no single country, but consists of 28 member states. Among these, the Netherlands (“Rotterdam effect”) and Germany are Indonesia’s most important trade partners.

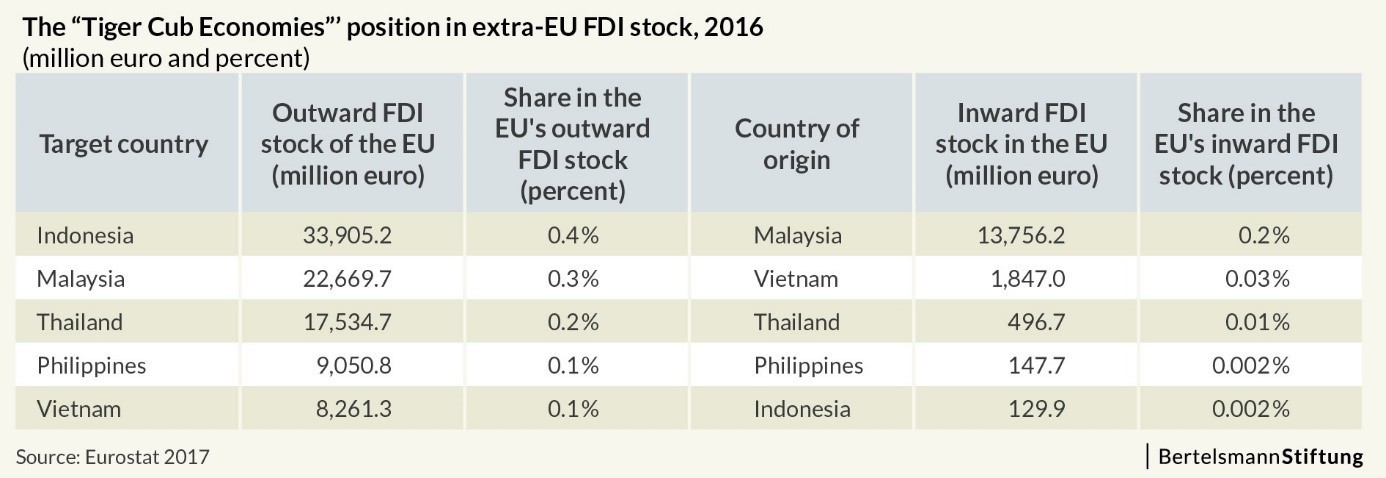

In contrast to extra-EU trade, Asia plays a rather subordinate role in regard to the EU’s foreign direct investment (FDI): the Asian share in the EU’s outward FDI stock was approximately 13 percent in 2015, and the Asian share in the EU’s inward FDI stock amounted to only 9 percent. While China is the most important destination in Asia for outward FDI by European business, the investment of Chinese companies in the EU accounts for less than one fifth of the EU’s FDI in China. Despite low numbers, there has been a heated debate about the activity of Chinese investors in the EU, since they are suspected to have political motives.

Indonesia has gained some importance as a target of FDI from the EU in Asia, ranking 6th in the region and 28th overall. The country has so far received the highest share in outward FDI from the EU among the tiger cub economies. The picture is the reverse when looking at Indonesian investment in the EU: the country holds a negligible 0.002 percent of the EU’s inward FDI stock. Out of the five tiger cubs, Malaysia plays the most important role as origin of FDI in the EU.

The analysis above shows that trade and investment relations between the EU and Indonesia are still underdeveloped. However, there are some factors allowing for the assumption that they have quite a bit room for growth:

First of all, Indonesia is still a rather closed economy. Further liberalization, if politically desired, could boost foreign trade and investment.

Second, the two regions have a combined population of well above 750 million people. Improved integration between the two markets would result in plenty of business opportunities.

Third, the EU is a developed region with high purchasing power. Indonesia is an emerging economy in the middle of its catching-up process with an ever growing middle class. Both sides could benefit from these different development stages, since they imply complementary supply and demand patterns rather than direct competition.

Hence, it is safe to say that economic relations between the EU and Indonesia could develop at a much more dynamic pace under more beneficial circumstances than there are currently. The free trade agreement currently under negotiation could be one key to unleashing this economic potential.

Looking ahead: Indonesia as a pillar in the EU’s “pivot to Asia”

As we have argued before, there are more than economic benefits to the EU’s FTAs with Asian countries, such as with Indonesia: Under President Trump, the United States – traditionally the centerpiece of the EU’s economic and external relations – appears to no longer be a reliable partner. Especially given recent developments which show that Trump is actually putting his protectionist trade policy ideas into practice.

Moreover, Asian countries have not been inactive with regard to regional trade. 16 of them, including Indonesia, China and India, are still negotiating the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). After the withdrawal of the United States, the remaining members of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) have overcome their difficulties and have decided to sign the agreement as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) on March 8, 2018 in Chile.

Finally, relations between the EU and China are getting more complicated, while moving from a more complementary partnership towards direct competition, which from an EU perspective takes place more often than not on an uneven playing field.

Given these developments, it is even more important than before for the EU to diversify its approach towards Asia and to look for other strong partners in the world’s current and future most dynamic region. The FTA with Indonesia could be a strategic move that would establish the world’s 4th most populous nation as a strong pillar of the EU’s “pivot to Asia”.

Dr. Cora Jungbluth is Project Manager in the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Global Economic Dynamics project. She specializes in macroeconomic analyses on Asia with a focus on regional trade agreements, global value chains and international investment.

Great post. While the global marketplace becomes more interconnected and accessible, the risks involved in doing business abroad are not to be taken lightly. I came across PointOne International, a trade development company that provides simple solutions to solve complex international business trading challenges.

[This comment has been edited by the administrator in order to remove a link.]