The G20 is Turning 20: Time to Take Stock of Multilateralism

On 30 November, heads of state and government will meet in Buenos Aires for this year’s G20 summit to discuss common solutions for global challenges. Yet things currently do not bode well for international cooperation. From the Paris climate agreements to the UN migration pact, global cooperation is increasingly being eroded by nations acting unilaterally. However, an international survey shows that the majority of citizens are calling for more courage in multilateralism.

International cooperation is under pressure: Populists in various countries are calling for a return to nationalism and withdrawal from international organizations. The Brexit campaign and calls for “America first!” are merely the best known examples.

However, the supporters of multilateralism are not sitting idly by. Together with Canada and Japan, German Foreign Minister Maas is calling for a new “Alliance for multilateralism.” The political discussion appears to be polarized – but what do the people think about this? How critical do they rate international cooperation in solving shared global problems? How aware is the public of international organisations and the issues they are dealing with? And what to people think of the G20 as one of the central international coordination mechanisms? A comparative international poll in Argentina, Germany, UK, Russia and USA provides answers.

Stronger together: Fervent support for international cooperation

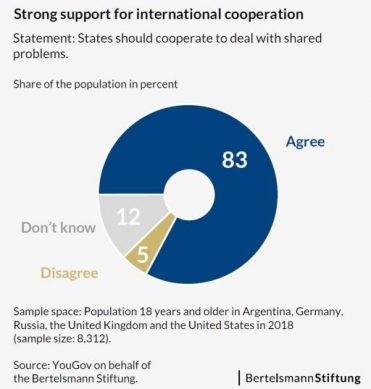

There is no sign that an end to the era of multilateralism is imminent. Instead, there is fundamentally very strong support for international collaboration, as 83 percent of citizens call on their governments to work together to solve shared global problems. Climate change, migration and (cyber-)terrorism – by itself, no single state can come up with effective responses to these and many other cross-border challenges. Even in the United States – the country with the lowest level of support for international cooperation – nearly three-quarters (73 percent) believe that states should engage in collective action. In the United Kingdom and Germany, more than 80 percent of the populace shares this belief (82 and 85 percent, respectively). And the approval rate even surpasses the 90-percent mark in Argentina and Russia.

This fundamental approval can be found in all societal groups. In fact, no single attribute by itself – whether age or gender or education level – correlates with a difference in attitudes toward multilateralism. On the other hand, one can see in all countries that the so-called “winners” of globalization are bigger supporters of international cooperation than the “losers” of globalization are. One can say that, the more people are convinced that globalization has a positive impact on their life, the more likely they are to support international cooperation.

What’s more, such support doesn’t automatically switch to opposition if one’s country has to make sacrifices instead of numbering among the winners. To be sure, the approval rate is lower. But the majority of people (58 percent) believe that it is sometimes necessary for their own country to accept short-term drawbacks and to (temporarily) prioritize a “global common good”.

Thus, support for the idea of multilateralism is strong. But can this high level of approval persist when the idea has been transformed into reality? The G20 is just about to celebrate its 20th anniversary – which seems like a good occasion to take stock. Has the G20 successfully managed to fully exploit the support that exists for international cooperation??

Reluctant support for the G20

On the whole, citizens have a rather positive image of the G20: While a bit less than half (45 percent) have a fundamentally favorable opinion of it, only one in five (20 percent) has an unfavorable opinion of it. In other words, the images of protests at the summits show only a small – albeit vocal – segment of society. What is striking, however, is that a third of respondents are not sure what they think of the G20, as they have not formed an opinion of it at all.

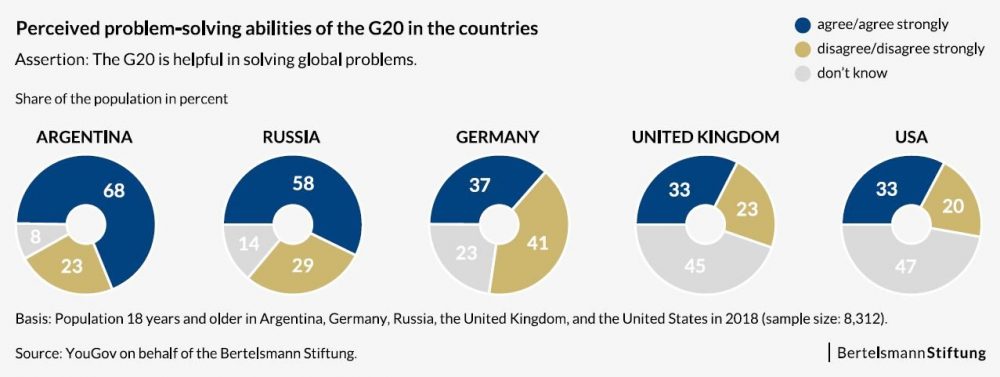

A similar picture emerges when people are asked to assess the quality of the G20’s work: When asked whether the G20 actually fulfills its pledge to contribute to solving global problems, 41 percent of respondents say they agree while over a quarter (27 percent) say they do not. But here, as well, almost a third of respondents cannot provide an assessment on this question, as they have not formed an opinion of it.

What can help us put this finding into context? The analysis reveals that the question of whether globalization has a positive impact on one’s own life also plays a key role in how one assesses the G20. Globalization’s winners consistently rate the G20 more favorably than globalization’s losers. Indeed, more than half (58 percent) of globalization’s losers tend to be have an unfavorable opinion of the G20, while only 9 percent of globalization’s winners have an unfavorable opinion of it.

“G20 … what’s that?” Low awareness of the G20 leads to questions regarding acceptance

A survey on the knowledge about and awareness of the G20 is sobering – but this should come as no surprise. People know extremely little about the G20. Three-quarters (74 percent) say they have heard of the G20 before, and more than one-third (36 percent) even think they can explain it.

But if they tried to do so, many would falter. Indeed, if you compare what people think they know with what they actually know, you will find a large disparity. Only a little more than one in a hundred (1.4 percent) can correctly answer four factual questions about the G20. What’s more, the picture doesn’t fundamentally change if you lower the bar a bit, as only one-quarter (26 percent) knows enough about the G20 to correctly answer three of the four questions. In fact, a quarter of all respondents had never heard of the term “G20,” and this was even the case for a majority of people in the United States (58 percent).

However, this should come as no surprise seeing that the media hardly cover the G20 at all and that there is hardly any shaping of public opinion of it or debate about its work. This is shown by the results of a media resonance analysis in 18 of the 19 member countries of the G20 for 2017: Of all articles in the G20 countries, only 0.35 percent touched on the G20 – a microscopically small proportion of the overall reporting. Germany, which held the presidency in 2017, and Argentina, which followed it in 2018, have the highest scores. In contrast, in the United States and the United Kingdom, where many people haven’t formed an opinion of the G20 yet, the G20’s media presence is below average (USA: 0.20 percent; UK: 0.19 percent).

In any case, this much is clear: People have little factual knowledge about the G20, and the media coverage of it is even smaller. Neither the G20’s low profile nor its low public visibility are proportionate to the importance of the issues that it addresses.

Thus, it is not surprising that people are undecided about whether their government should follow the recommendations of the G20 – regardless of whether it would be in the interest of their own country. This question provides important clues about whether the G20 enjoys public acceptance. However, people who know little about the processes, structures and procedures of the G20 and who also hear practically nothing about it in public discourse can hardly form an opinion regarding whether it should be deemed fair and is bringing about good results. Survey results reveal the fracturing within the population: While one-third (34 percent) of people are in favor of following the recommendations of the G20 quite independently of their own national interests, one-third (33 percent) are against doing so and one-third is uncertain (33 percent).

On this question, as well, American respondents showed great indifference and indecision. This mirrors a pattern that runs through many individual questions and that seems to paint a critical overall picture of debates about multilateralism in the United States. And this is reason enough to take a closer look at this former champion of multilateralism and major supporter of the liberal, rule-based world order.

What now?

Explain yourself and own the debate: The media resonance analysis has convincingly shown just how meager the coverage of the G20 and other international organizations is. In fact, they hardly appear in the public debate at all. People are not very familiar with them, they have hardly any practical knowledge about them and, more importantly, they are often unable to form their own opinions of them. International organizations must work on bolstering their presence in the public debate. They themselves should communicate their goals and working methods to the public. If they don’t, people will either remain uncertain about whether to accept the organizations or become vulnerable to populist cries for withdrawing into the national sphere – even though they are fundamentally convinced that global problems can’t be solved by unilateral action. International organisations as well as governments of member countries should not allow others to shape the debate about who they are, how they work and what their goals are, they should become more active themselves.

Make globalization fairer: The biggest fans of international cooperation and the G20 are the so-called “winners” of globalization. As a general rule, the more people are convinced that globalization has a positive impact on their own life, the more likely they are to support international cooperation as well as the G20. Nation-states and international organizations should ensure that globalization not only works for cosmopolitan avant-gardes, but for as many people as possible. The final declaration of the heads of state and government after the 2017 summit in Hamburg shows that the G20 also recognizes this. “The G20 is determined to shape globalization to benefit all people,” it states, adding: “Most importantly, we need to better enable our people to seize its opportunities.”

Christina Tillmann is Director of the Future of Democracy Program at the Bertelsmann Stiftung.