New Walls I: Militarizing Borders in Europe

What has become of the hope for freedom in a borderless world, thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall? Instead of disappearing, more and more hard border fortifications arise. — Episode 1 of our “New Walls” series.

After the end of the Cold War, borders were seen as a legacy of the past. The new freedom of movement inside the EU served as an attractive model for the former Communist bloc. Also, from a global perspective, borders were meant to be lifted as much as possible to fulfill the promise of globalization and liberal democracy.

However, this perspective changed with the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Borders transformed from static lines to deterritorialized surveillance networks. The ambition was to combine international mobility with a new type of electronic controls, which involve both state actors and private companies. Any kind of transnational flow, be it goods, capital or persons, should be subject to seamless documentation, screening and authorization right from the source to its final destination.

The fall of the Berlin Wall sparked hopes of a new, borderless and peaceful global society. Many developments since then fostered this dream, ranging from European integration and digital knowledge sharing to the rise of low- and middle-income countries into the ranks of leading world economies. 30 years later, we have witnessed not only the construction of new physical barriers, but also new divides like digital censorship, social media taxes, and protectionist trade policies. By barring goods, ideas and aspirations from spreading freely across countries, “new borders” contribute to unequal access to public goods, regional disintegration, disinformation, and disrespect for human rights. We ought to get to know them better – in our mini-series “New walls”.

Yet instead of reassuring liberal democracies in their way of life through new security technologies, the so-called War on Terrorism fueled a sense of paranoia and erosion of political freedoms. By the late 2000s, economic shocks, rising inequality and a growing political backlash against globalization led to a resurgence of nationalism in the West, while China and Russia became more vocal in their challenge of the established global order.

Worldwide spread of border installations

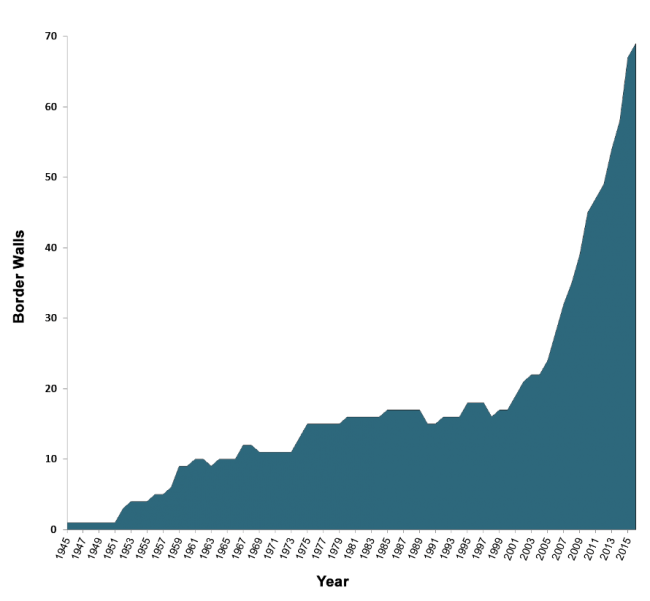

Nowadays, borders have come to highlight the crisis of liberal democracy and the growing divisions between cosmopolitan elites and „ordinary people“, which predominantly live in smaller towns or the country-side. The resurrection of physical borders has taken on an outsized symbolic importance. Already at the beginning of the 2010s, the number of international hard border fortifications had gone up from 15 at the end of the Cold War to over 70, comprising a total of more than 30.000 kilometers.

Since then, border installations have rapidly spread further around the world due to violent conflicts and population movements, among others, between Russia and Ukraine, Pakistan and Afghanistan, Bangladesh and India, Saudi Arabia and Iraq, Israel and Egypt or between Turkey and Syria as well as Iran. And since the election of Donald Trump, his promise to build a beautiful wall towards Mexico polarized U.S. politics as well as relations with Central America. In this light, new border installations are either criticized as an outgrowth of senseless populism with inhuman consequences on vulnerable refugees or as the last line of defense against globalization, unchecked immigration and even moral decay.

The debate over the shifting meaning of borders has been particularly intense in Europe. Over the last three decades, the process of European integration lifted, transfigured and reimposed multiple borders. The demolition of the infamous Iron Curtain and the gradual extension of the Schengen zone led to dramatic rise in personal mobility in Central and Eastern Europe. Yet European integration has also meant to reimpose and upgrade border controls between former neighbors in the region, such as between Poland and Ukraine or between different member states of former Yugoslavia. (Re-)gaining freedom of movement is one of the most important reasons for countries from South-Eastern Europe to maintain their membership applications to the EU. However, the constant drain of emigration of highly qualified citizens to Western Europe – amounting to almost 8 percent of the total population according to the regional analysis of the Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI) – has also given rise to deep resentment, increasing inequality and rising nationalism in various Central and South-Eastern European countries.

Illiberal drift in Central Eastern and South-Eastern Europe

The migration crisis since 2015 has brought out and exacerbated these underlying tensions. In the name of protecting a borderless EU from within, European states have been pushed to aggressive external border policies. This manifested itself a rapid spread of new hard border fences across South-Eastern Europe, such between Hungary and Serbia, Slovenia and Croatia or between Greece and North-Macedonia. Physical installations have been shadowed by a move to very aggressive border-policing tactics. Related violations of human rights of migrants and challenges to the rule of law have been mostly accepted by other European member states. At the same time, illiberal populist movements redirected the dissatisfaction with emigration and economic inequality towards migrants and other convenient scapegoats.

As a result, the historical transformation towards liberal democracy in Central Eastern and South-Eastern Europe has come under severe stress, as illustrated by the criminalization of nongovernmental organizations, the repression of political opposition and freedom of speech, coordinated media campaigns to blame migrants alongside “foreign elites”, or the state-sponsorship of authoritarian border militia. The BTI and its country reports provide a systematic and alarming overview of the ongoing illiberal drift in the region, which has a particular momentum in Hungary and Poland, but is unfortunately not limited to these countries. In fact, one could see the rise of new alliances or political friendships well beyond the region, reaching to old EU member states, such as Italy, or indeed to nationalist movements in the US or also Russia.

Borders indicate the health of liberal democracy

To date, the feared transnational alliance between Russia, various Central and South-Eastern European Countries as well as Italy has not materialized to the full. Yet it also remains to be seen whether international organizations, such as the European Union and the Council of Europe, will be able to mobilize more effective countermeasures. The last European elections gave some hope that populists are faced with a renewed political opposition from liberal forces.

What is clear is that the ever-changing role of borders serves as an indicator for the health of liberal democracy. Borders are neither helpful to dramatize the role of national identity or sovereignty, nor can they be rejected as remnants of the past that need to be swept away in the name of globalization. The political discourse over the meaning of borders should rather be deflated and redirected to other, more internal forms of cohesion and trust that are essential for open and liberal societies.