Longing for Status. Russia Celebrates its BRICS Chairmanship

“BRICS is a pillar of the multipolar world.” With these words, Foreign Minister Lavrov inaugurated Russia’s BRICS chairmanship in 2024. It is intended to be a milestone in the fight against U.S. hegemony and for a new multipolar world order. Though the enthusiasm with which Moscow pursues this goal is by no means shared by all BRICS members. This does not deter Russia, as it cannot afford to be selective given the international headwinds it has faced since its invasion of Ukraine: apart from a brotherhood-in-arms with North Korea and Iran, Moscow remains largely isolated, with Belarus tagging along. Together, they have formed a veritable “Axis of Evil.” This drives Russia to invest heavily in BRICS, whose chairmanship it assumed in turn: 250 activities are planned for 2024, so many that most BRICS members are feeling overwhelmed. The highlight will be the summit of heads of state and government from October 22 to 24 in Kazan.

BRICS – A Heterogeneous Discussion Platform

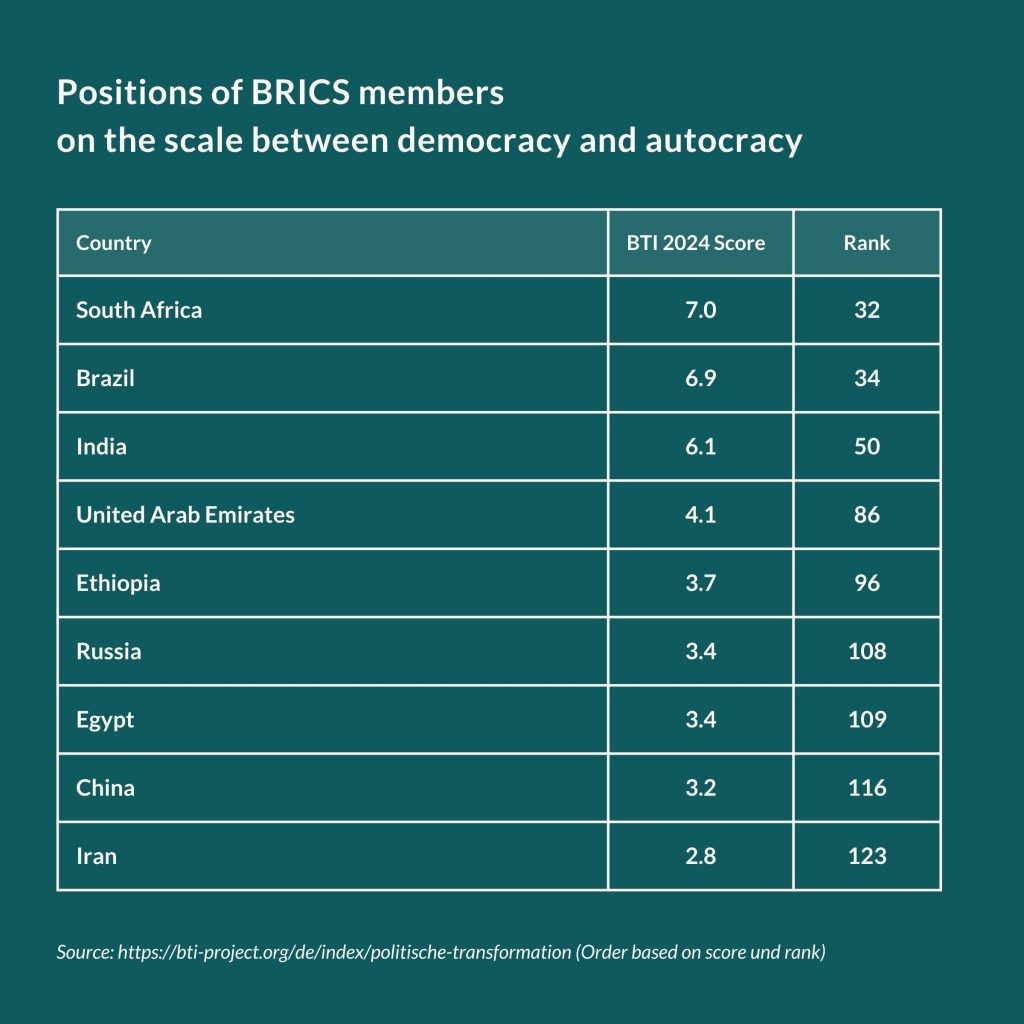

The BRICS statistics are certainly impressive: after expanding to include four more states in early 2024, they now represent over 45% of the world’s population, 36% of global economic output (GDP, based on the purchasing power parity favored by BRICS states, which make the poor richer and the rich poorer), and 25% of global trade, not to mention their control of key natural resources such as oil. However, this alone does not translate into collective power, as BRICS is a rather economically and politically heterogeneous group. The 2024 Bertelsmann Transformation Index data shows that the current BRICS members cover almost the entire spectrum of the 137 countries assessed in terms of “political transformation,” which ranges from stateness and rule of law to political participation and social integration.

Two countries invited to join at the end of 2023 represent the political extremes between democracy and autocracy even more strikingly: Argentina (7.45/22), which rejected the invitation after the election of new president Milei, and Saudi Arabia (2.73/124), which remains undecided.

The political heterogeneity means BRICS lacks a common normative basis, let alone a foundational document. The consensus is limited to the guiding principle outlined by Foreign Minister Lavrov in May 2024: “The only condition is that you agree to work based on the fundamental principle of the sovereign equality of states,” which, according to him, the West is incapable of doing. In addition to a normative foundation, BRICS also lacks common institutions. It remains little more than a dialogue platform, similar to the G-77 from 1964, which comprises 134 members (including all BRICS members except Russia). Like the G-77, BRICS membership requires neither costs nor commitments. This explains the long list of more than 30 countries aspiring to join, including NATO member Turkey. It remains to be seen how these membership applications will be handled in Kazan, as BRICS faces the dilemma of balancing expansion with deepening cooperation. Russia prefers the “BRICS-Partner” model to aim focus at its priority: sanctions management. China pushes for expansion to create the broadest possible platform for its global ambitions, while relying unilaterally on its growing economic clout.

While there may be different preferences in this regard, Moscow and Beijing—along with Teheran—are fully aligned on one point: they form the core of the anti-hegemonic, meaning anti-Western, “vanguard of the world majority,” as described by Yuri Ushakov, Putin’s foreign policy expert. Their goal is to create a new world order, not reform the existing one. The majority of BRICS, however, does not follow this goal. They are committed to India’s principle of “multi-alignment,” which, despite all its multipolar sympathies, includes the West.

Russian Ambitions as Vanguard of the “World Majority”

The “world majority” has become Moscow’s preferred antidote to its international isolation, with BRICS serving as the “global organizing principle for the Global South and East,” according to Foreign Minister Lavrov. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, anti-colonial rhetoric regarding the Global South from past decades has also seen a revival. However, the anti-colonial stance is mere window dressing by the last remaining colonial power, especially since Russia discarded the Global South for decades as an unnecessary and costly Soviet burden (as evidenced by its minimal development aid to this day, at no more than 0.05% of its GDP).

Russia’s many activities during its BRICS chairmanship aim at both this “world majority” and its domestic audience, demonstrating that there is an alternative reality beyond the West. These include groundbreaking initiatives like the first “BRICS+ Fashion Summit,” a forum of BRICS partner cities, a BRICS film festival, and a BRICS theater school festival. A highlight on Russia’s path to “sports multipolarity” was the BRICS “Games of the Future” in June 2024 in Kazan, held for the first time with supposedly 82 participating nations. For Russian (and Belarusian) athletes, the games offered a substitute for being banned from the Olympics, while other nations participated more as a formality. Unsurprisingly, Russia won nearly half of the 1,161 medals awarded (507), with Belarus taking second place with 247, while China managed to win only 61 medals.

However, the momentum for “sports multipolarity” quickly faded: the “World Friendship Games,” scheduled for September, a clear revival of the socialist-era Spartakiad games with the lure of $50 million in prize money, were canceled after protests from the IOC. Similarly, Moscow’s attempts to revive the former Eastern Bloc’s “Intervision Song Contest” under BRICS met little success.

On the Road to “Financial Multipolarity”?

The “overarching theme” of Russia’s chairmanship, according to Finance Minister Siluanov, is the creation of a new international financial architecture independent of the U.S. dollar. This comes as no surprise, as mitigating the effects of Western sanctions, especially in the financial sector, has become a matter of economic survival for Russia.

All BRICS members undoubtedly share unease over the dominance of the U.S. dollar, especially as the U.S. has increasingly wielded it as a political weapon since 2010. At that time, BRICS made their first moves toward “de-dollarization.” However, all members—except Russia—are also united in their desire to avoid unpredictable risks and unacceptable costs in this fight against the U.S. dollar. They seek additional options rather than outright replacement.

The chances for this are not particularly good, as BRICS’ significant economic weight is not reflected in international financial markets: the U.S. dollar accounts for 58% of global foreign exchange reserves (euro 20%), 88% of currency trades (euro 31%), and 54% of export transactions (euro 30%). The BRICS “New Development Bank,” founded in 2015 with $100 billion in capital, operates almost entirely in U.S. dollars and complies with Western sanctions: projects in Russia have been suspended, and projects with Russian participation in third countries have been postponed. The BRICS currency fund (Contingent Reserve Arrangement), also established in 2015, has been frozen by participating central banks, and balance of payments assistance has yet to be provided.

Two “de-dollarization” projects are the focus of preparations for the summit in Kazan: increasing the share of national currencies in trade both among BRICS members and beyond, and expanding BRICS financial infrastructure. For Russia, both are intended to mitigate the impact of financial sanctions, though their implementation is frequently hampered by these same sanctions.

According to Putin, by early 2024, Russia had already conducted 90% of its trade with China in rubles and yuan, serving as a model for trade among BRICS members and the Eurasian Economic Union. However, since December 2023, U.S. secondary sanctions have increasingly hindered Russia’s dealings with correspondent banks in China, Turkey, the UAE, and India, as well as even Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. These banks have rejected requests to open accounts for Russian business partners, suspended transactions, extended payment processing times, and scrutinized Russian partners for ties to the defense industry and sanctions lists. This also applied to Russian payments in yuan.

Similar issues arise in efforts to establish an independent financial transaction communication network after Russian banks were excluded from SWIFT. A “BRICS Bridge” platform for multilateral payments is planned to link national systems for bank information transfer, but this faces the problem that the Russian service provider is also subject to U.S. sanctions. Alternative solutions such as payments via blockchain technology, cryptocurrencies, and stablecoins have been considered, though the likelihood of supranational currency surrogates succeeding is slim in an association whose members prioritize national sovereignty.

An additional systemic issue related to de-dollarization has emerged in Russia’s trade with India. As India refuses to conduct its expanded trade with Russia in yuan, Moscow faces the dilemma of how to use its substantial rupee surplus, which by 2024 exceeds $57 billion. In this context, Moscow has repeatedly stressed the need for a (synthetic) BRICS reserve currency to address such trade imbalances. Surprisingly, despite all their aversion to the West, BRICS has officially cited the ECU (European Currency Unit), the predecessor of the euro from 1979, as a model.

Dreams and Reality

The failed attempt to establish a BRICS rating agency demonstrated how difficult it is to circumvent or even dismantle the established financial order. Further-reaching projects, such as the creation of a fully-fledged BRICS financial system, require investments in both money and trust—resources that the BRICS members are, predictably, not prepared to commit.

Even Russian observers admit that overcoming the dependency on the US dollar and Western financial institutions would require the creation of a completely self-sufficient interregional BRICS financial architecture, ideally with an interregional BRICS currency. Only then, they argue, could “financial multipolarity” be achieved. However, the necessary conditions for this are entirely lacking.

Nonetheless, this did not stop Foreign Minister Lavrov from declaring at the start of Russia’s BRICS chairmanship: “From now on, the global economic system will develop along different paths.” Such statements, however, exist in the lofty heights of anti-Western war rhetoric, something Lavrov cultivates with particular zeal. In the realm of harsh financial realities, things look quite different. Lavrov’s deputy and Russia’s BRICS Sherpa, Sergei Ryabkov, tempered expectations mid-year, stating: “Maybe there will be no decisions that will radically transform everything. Probably, this is not necessary. After all, this is such a sensitive area where evolutionary progress is optimal.” If only Russia had adhered to this maxim on other occasions…

First published on Global Policy.