Courteously Turning Away: How Latin America Is Building Up New Partnerships

Latin America is at a geopolitical watershed. Instead of continuing to subordinate itself to the interests of the US and Europe, the region is quietly but resolutely seeking to forge new partnerships. While its tone remains diplomatic, the direction is clear: shifting away from long-held dependencies and towards greater independence and relationships that are on an equal footing. What emerges is not a revolt but rather a quiet emancipation.

Since Donald Trump’s return to the White House, the foreign policy realignment of many Latin American countries has entered a new phase – not only as a direct reaction to the US president and his policies, but also as an expression of the nations’ growing self-confidence. In the midst of an increasingly multipolar world order, the countries between Mexico and Chile are trying to reshape their relations with the global centers of power. There is a clear trend, particularly in countries led by left-wing governments: less subjugation combined with more independence. Instead of unilaterally tying themselves to the US as in previous decades, many governments are actively seeking economic and political alternatives – with China, the EU or by boosting regional ties. This is not about making a radical break, but the search for a new and more equal pathway.

However, the fronts are far from homogeneous. Latin America is not a homogeneous bloc but a region with strongly divergent political, economic and social developments. This trend is reflected in the Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI) 2024, which clearly highlights uneven political developments across Latin America. While countries such as Colombia and Chile are making progress in terms of democratization and governance, others, such as El Salvador, show authoritarian tendencies that affect political stability.

The region remains deeply divided ideologically, economically and strategically. Conservatively governed countries such as Ecuador and Peru, as well as populist-led El Salvador under Nayib Bukele, and even left-leaning Honduras, are intensifying their cooperation with the United States, often in the field of security policy and with the involvement of U.S. military advisors. In contrast, progressive governments, such as those in Brazil, Colombia and Chile, are increasingly seeking to connect with other global regions. However, this division does not run along simple pro- or anti-US lines but concerns how much sovereignty a country can secure in an international system characterized by dependencies and competition.

New self-confidence, old patterns

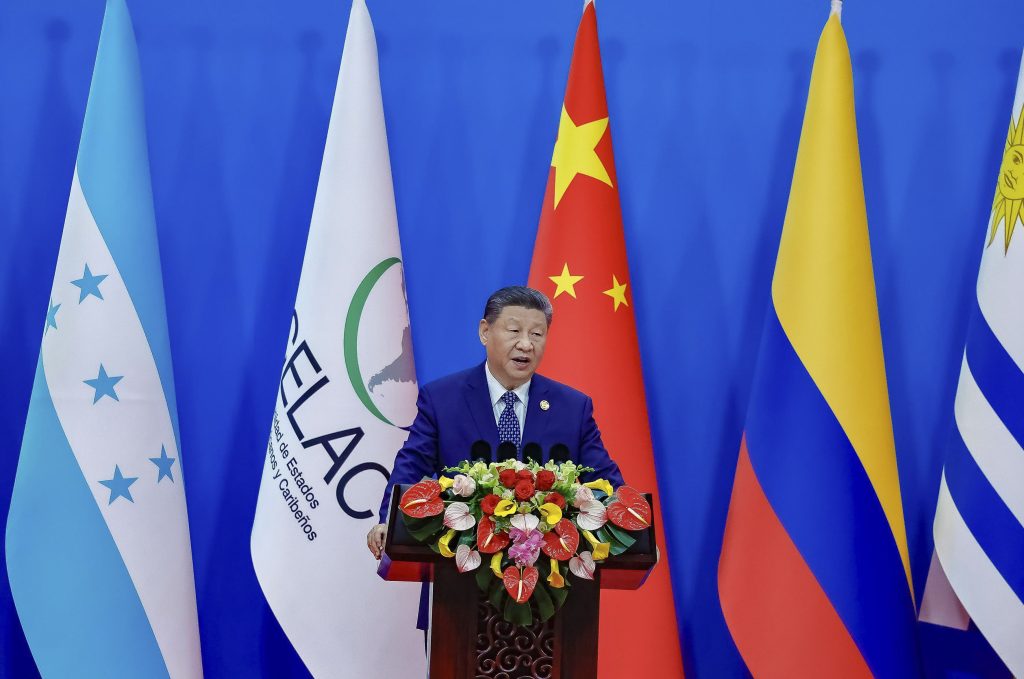

One of the most visible signs of Latin America’s current geopolitical reorientation is the growing importance of China. In forums such as the China-CELAC meeting, which took place in Beijing in May, it is clear how intensive cooperation already is – not only at an economic level, but also regarding education and security policy. China is enticing partners with loans, investments in infrastructure, digital technologies, education and green energy. In recent years, it has become the leading trading power in the region, building mega ports and metros, and already replacing the US as the most important partner in countries such as Brazil, Peru and Chile. More than two thirds of Latin American countries are now part of China’s “New Silk Road”, a global infrastructure initiative that has been expanding strategic access to markets and raw materials since 2013.

This turn towards China has a long history: trade relations intensified in the early 2000s, driven by China’s growing need for raw materials and Latin America’s demand for infrastructure investments. The New Silk Road initiative offered many countries a welcome alternative to Western offers, which were often tied to political conditions.

Against this backdrop, Europe has emerged as just another player vying for influence in the region. In Berlin, awareness of the strategic importance of Latin America has increased. The current coalition agreement emphasizes the “special importance” of the continent, calls for the conclusion of the EU-Mercosur agreement and explicitly names Brazil, Mexico, Argentina and Colombia as key partners. The focus is on raw materials such as lithium, green energy and the expansion of strategic value chains. Germany is pushing for concrete economic cooperation, for example, in hydrogen or fair raw material partnerships. But here too, the success of European offers will depend on whether they are actually understood as a partnership of equals – as opposed to yet another expression of Europe’s interest in cornering raw materials. Latin America countries are aware of their strategic role – and of the cards in their hands when it comes to negotiations.

The relationship with Europe also has a historic dimension – and it is characterized by contradictions. The EU-Mercosur agreement has been under negotiation since the 1990s, with a political agreement reached in 2019. However, it is still on ice. While the EU is promoting it as a strategic partnership, skepticism is growing in Latin America. Many fear that it will reinforce existing imbalances. It favors the export of agricultural raw materials and the import of European industrial products – a classic North-South division of labor that comes at the expense of regional value creation and sustainable development. Critics do not see this as a genuine partnership, but rather as a new form of asymmetrical interests. Small farmers’ associations and environmental organizations also warn of increasing deforestation and growing land conflicts and point to soya cultivation and beef exports or exotic fruits such as the acai berry. Although the agreement contains sustainability clauses, these are not enforceable. The lack of transparency in the negotiation process is sparking mistrust in the region. Mercosur, once seen as the driving force behind Latin American independence, is increasingly perceived as an over-regulated bloc that restricts the scope for action of individual countries – which is prompting Uruguay, for example, to seek its own trade agreement with China.

At the same time, authoritarian states such as Nicaragua are using the geopolitical opening to break off relations with Taiwan and forge closer ties with China. This is often done with a nod to Beijing’s rhetoric of mutual respect and non-interference, values that resonate in a region with a long history of external influence. However, using state sovereignty as a cover for restricting critical voices at home and abroad is an essential tool for autocratic regimes such as Nicaragua and China. In the Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI), for example, both countries consistently score low on the separation of powers, freedom of expression and freedom of the press, as well as the involvement of civil society actors.

Such examples show that Latin America is not a geopolitical bloc. National interests, domestic political constellations and foreign trade strategies all play a part in the region.

Mexico has a special role to play in the current delicate context. President Claudia Sheinbaum is trying to take advantage of the economic benefits of the North American T-MEC agreement without allowing herself to be completely drawn into Washington’s strategic goals. Her “Plan Mexico” aims to reindustrialize the country and reduce its dependence on Asian, particularly Chinese, imports. On the one hand, this is in line with the US, which sees Mexico as a potential gateway for Chinese products into the North American market and accuses Chinese companies of strategically using the country as a hub. On the other hand, the Mexican government rejects these accusations. Meanwhile, Mexico is also presenting itself in a new way: as self-confident, but not confrontational.

Sovereignty through diversity

A new foreign policy paradigm appears to be gaining ground in the region: sovereignty through diversity. Latin America is not seeking a break with the US – its economic and cultural ties are too deep for that. However, it is also no longer seeking unconditional allegiance but governments are opting for a pragmatic foreign policy. The recently deceased former Uruguayan President Pepe Mujica exemplified this principle. He questioned the “American way of life,” criticized the obsession with consumerism and individualism, and emphasized that true progress lies in the dignity and self-determination of peoples. His idea of an independent but interconnected Latin American policy now shapes the thinking of many heads of state on the continent – whether consciously or not.

However, this new course is not without its risks. Too much proximity to China can result in new dependencies that could be just as restrictive as the region’s previous reliance on Washington. The challenge is to cooperate with all players without becoming subservient to any of them. Gustavo Petro’s appearance at the Beijing CELAC Summit underlines this ambition. He spoke out in favor of multilateral cooperation that is not subordinate to any major power. Together with Brazil’s President Lula da Silva and Chilean President Gabriel Boric, he emphasized that Latin America was claiming its place in the global power structure – not as a supplicant, but as a partner with its own ideas of development, peace and prosperity.

Change through diversification

In the new geopolitical framework, Latin America is thus in the process of redefining its role. It is no longer merely the receptor of foreign policy interests but increasingly a strategic player with its own agenda. However, the reality remains complex. While some states are opening up in terms of foreign policy and cultivating diplomatic diversity, others are falling back into old patterns of military cooperation with the US – such as Ecuador, Panama and Peru. All three recently negotiated joint maneuvers, technology exchanges and military training with the Pentagon.

Latin American countries currently find themselves at a geopolitical crossroads. In the midst of global competition between China, the US and the EU, there is an opportunity to break out of historical dependencies and shape an independent role in world politics. The path to this goal is full of pitfalls, contradictions and setbacks. However, its progress is also an expression of a region that is once again becoming more aware of its importance – as a resource-rich, politically diverse and culturally self-confident zone between the world’s geopolitical heavyweights.

It remains to be seen whether this new Latin American urge to assert itself will last. The temptation to turn to the economically more powerful remains great, regardless of whether these power centers are in Washington, Beijing, or Brussels. However, the region seems to have understood that geopolitical independence is not achieved through loud rhetoric, but rather through quiet but consistent diversification. The fact that Latin America is now asking who it wants to work with, rather than who it has to work with, may mark the beginning of a new chapter – one that is less about dependency and more about dealing with partners on an equal footing. This is a tentative change – but it is a start.

First published on Latinoamérica21