Georgia: Backsliding on Justice?

On 10 June 2017, thousands of Georgians protested on the streets of Tbilisi in support of two young rappers, members of the group Birja Mafia, who were arrested on drugs charges that they say were trumped up. The protests marked another step in Georgians’ decline in trust for their law enforcement system.

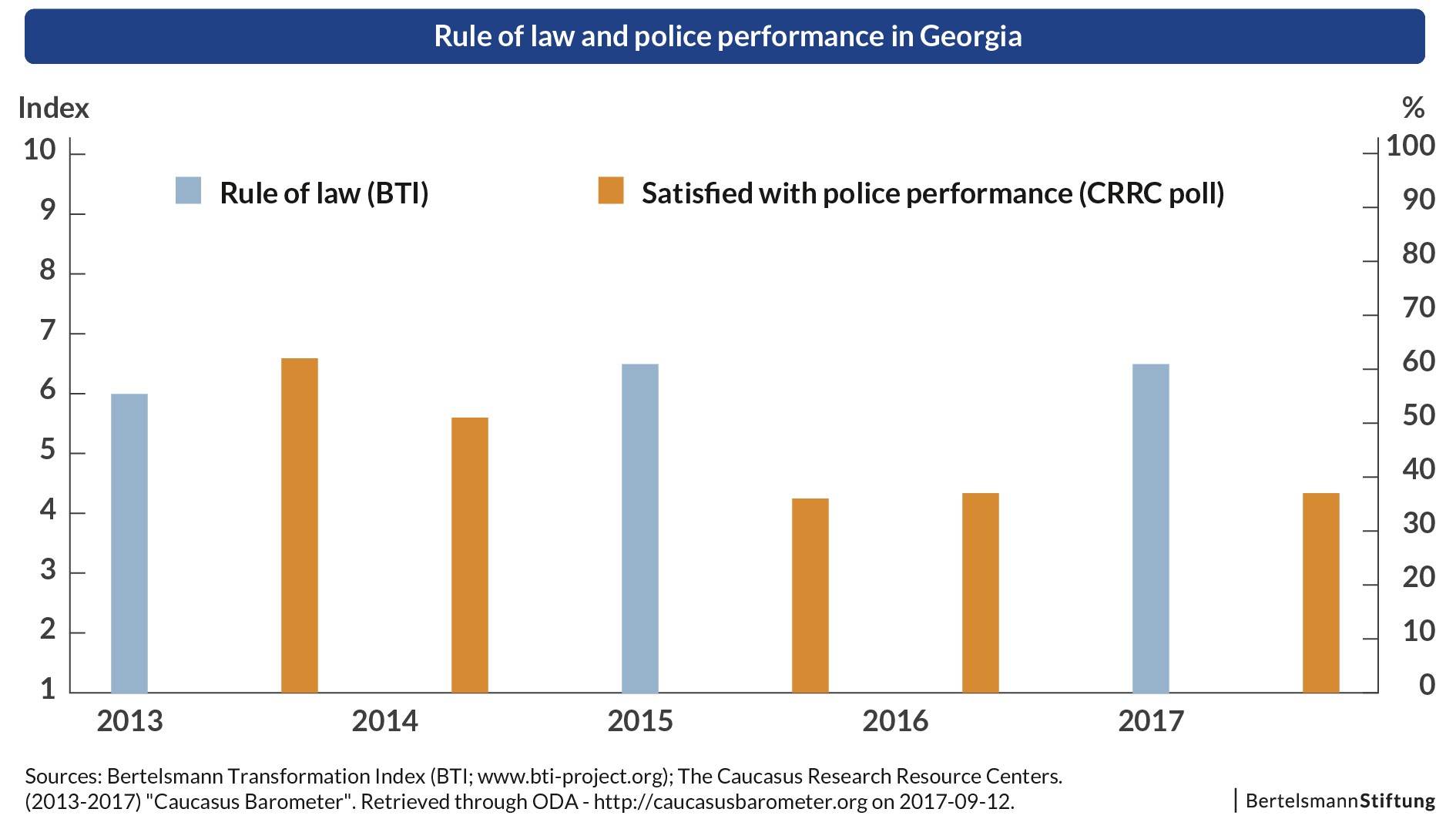

Former President Mikheil Saakashvili’s successful police reforms in the first decade of the twenty-first century served as a model for reform in transition countries, but the gains may have been short lived: By April 2017, only 38% of Georgians rated police performance well or very well, down from 60% as recently as November 2013. Meanwhile, only 13% rated the performance of both the courts and the Office of the Chief Prosecutor well or very well; 27% said the courts performed badly or very badly, while 19% said the same of the Office of the Chief Prosecutor. Is the rule of law in Georgia on a downward trend?

Georgia scored 6.5 on the “Rule of Law” criterion in the Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI) 2016, a respectable showing that placed it along with 22 other transitional and developing countries in the Sound category, below nine countries ranked as Excellent but above the remaining 97 countries designated Fair, Flawed, or Poor. However, the report notes problems both with the prosecution of office abuse and the independence of the judiciary, two issues that are contributing to the current deterioration in public confidence.

The Birja Mafia affair is not the only high-profile case to hit the headlines; in May, Azerbaijani journalist Afgan Mukhtarli was abducted in Tbilisi and transferred to prison in Azerbaijan, and accusations of complicity among the Georgian police led to the suspension of the head of the Border Police and the chief of Counterintelligence in July. Mukhtarli’s lawyers and wife say that the journalist’s abductors wore the uniform of the Georgian police. And in June, one of Tbilisi’s police chiefs was suspended after Georgian media released a video appearing to show police abuse, in a March case in which Shota Pakeliani ended up in a coma after receiving injuries in police custody. In both cases, authorities took action after public outcry, but critics say that this happens too rarely, and that when it does, the consequences are insufficiently severe.

Difficult Reforms

In 2015, the Prosecutor’s Office announced plans for a Department for Investigation into Crimes Committed throughout the Judicial Process – but since the Prosecutor’s Office is frequently accused of having political motivations, this department may be insufficient to solve the problem. In 2016, investigations were opened into 173 cases of alleged police mistreatment, but none for police brutality or torture – only for the less serious crime of “exceeding official powers.” Only five investigations led to criminal proceedings, and only two resulted in guilty verdicts. In its 2016/2017 annual report, Amnesty International raised concerns about the Georgian government’s failure to move on legislation to create an independent mechanism for investigating law enforcement bodies’ human rights violations.

Georgia received visa-free travel to the European Union in March 2017, and its Association Agreement with the EU entered into force in July 2016. Georgians overwhelmingly support eventual EU membership – in a poll taken in February and March this year, 90% of respondents favored EU membership. So, although accession is not on the EU’s radar just yet, the Georgian government should be strongly motivated to comply with the Association Agenda, which includes reforming the prosecution service. Efforts have begun to do that. The Prosecutor’s Office was separated from the Ministry of Justice in 2012, and in early 2016, a Prosecutorial Council and a Consultation Board were established to increase the office’s independence. In a January 2017 report, the Council’s anti-corruption body, the Group of States against Corruption (GRECO), had praise for Georgia’s progress in reducing corruption, and welcomed the country’s efforts to reform its prosecution service. But GRECO noted that further steps needed to be taken to fully implement reforms and to reduce the influence of the executive and the legislature on high-level prosecutorial appointments and on the activity of the Prosecutorial Council.

De-Politicization of Justice

The same kind of political linkages contribute to the problems within the police force. The position of top police officers is dependent on the will of the interior minister, which undermines the independence of the force. In the courts, too, the legacy of politicization persists from the administration of Saakashvili, although the new government has taken some steps to improve the situation. The Public Defender’s Office is one bright spot – responsible for overseeing human rights and freedoms in Georgia, it enjoys broad public support, but its recommendations are not implemented often enough.

De-politicization of justice needs to be a priority of the ruling Georgian Dream party, for the sake of the public at large, the country’s EU hopes, and perhaps even the party’s own political fortunes. The former governing party, Saakashvili’s United National Movement, found to its cost that failing to provide adequate support for the rule of law can have political consequences – widely publicized cases of prison abuse and police violence contributed to the party’s loss of public trust and eventual ouster in 2012. If the current government cannot improve public confidence in the system, it might find that history can repeat itself.