Russian Presidential Election: To the Victor, Stagnation

Putin will remain Russia’s strong man for another six years. But his muscle-flexing on the international stage is designed to divert attention from the country’s dismal economic outlook.

A key feature of democratic elections, according to Polish-American political scientist Adam Przeworski, is their “institutionalized uncertainty”: Anyone can win. There is no question that Russia’s presidential election scheduled for March 2018 fails to meet this criterion. The outcome is a foregone conclusion; all that remains to be seen is whether the incumbent Vladimir Putin will win the election with 60 or 70 percent of the votes. In the run-up to the last presidential election back in 2012, the prospect of having to endure not just six, but in all likelihood twelve more years of Putin rule after Dmitry Medvedev played a key part in triggering the vigorous but short-lived mass protests of the urban middle classes.

That said, aside from the stultifying continuity it promises, the election in March will in fact usher in a period of uncertainty in that it marks the beginning of what can only be assumed to be Putin’s last term in office – which from the outset is sure to spark intense political maneuvering and jostling for power with an eye to the subsequent period. This will take place against the backdrop of a political balance which can at best be described as mixed, and an accretion of problems demanding far-reaching decisions.

Strong state, weak economy

On one hand, it is true that Putin and his regime have succeeded in bringing about much-needed political stability and in “strengthening state power”, as Putin never tires of reiterating. However, this has come at a high cost: draconian laws, an all-pervading surveillance and security apparatus, travel bans for millions of public officials and systematic repression of any form of protest. Whereas the oft-cited pretexts for these measures, ranging from the fallout of the Arab Spring to the Euromaidan protests in Kiev, resonate with a population for whom the “Time of Troubles” of the 1990s is still a very recent memory, this approach hardly promises a sustainable consensus.

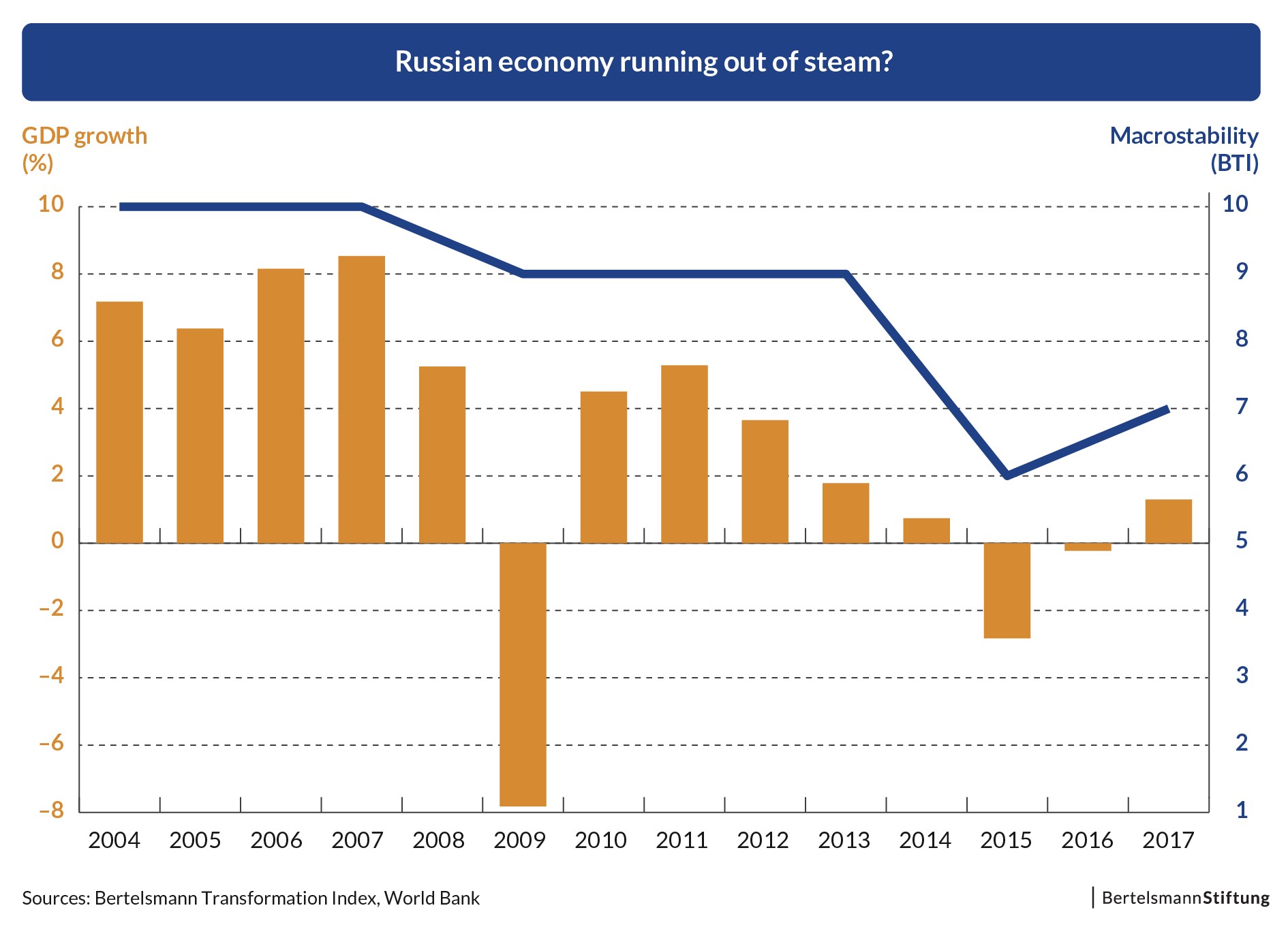

Such acceptance requires prospects for economic and social development, which have been in short supply since the profound crisis of 2009, which saw GDP plummet by 7.8 percent. This was followed by a short-lived recovery before another recession kicked in in 2014, from which the country was only able to emerge in 2017 with growth of 1.8 percent. The outlook is certainly anything but encouraging. As shown by the latest Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI), the latest recession inflicted lasting damage on Russia’s macro-economic prospects.

The indicator Macrostability dropped from ten to six in the period 2006 to 20016, and the new data for 2018 still don’t show significant recovery. Russia’s Central Bank has warned that without far-reaching reforms, even at an oil price of $100 per barrel (compared to the current price of $60) growth cannot be expected to exceed 1.5 to 2 percent in the years to come. Accordingly it is little wonder that Russia’s share of global GDP has been falling for years, from 3.95 percent in 2008 to just 3.11 percent in 2017. Quite how Russia is to achieve its officially stated goal of becoming one of the world’s five largest economies under these circumstances remains Putin’s secret.

Economic policy on an uncertain course

Another question mark hangs over the economic policy direction Putin intends to adopt after his re-election. In fact, he has had two detailed plans up his sleeve since May 2017: one neoliberal in nature, designed by former finance minister Alexei Kudrin to improve working conditions for the private sector, the other with a Keynesian dirigiste focus drawn up by Boris Titov, who was appointed ombudsman for entrepreneurs’ rights by Putin in 2016 and will run as one of his rival candidates in March 2018. Putin has, in turns, shown favor both for Titov’s approach, when advocating ambitious public infrastructure projects or vaunting the achievements of the state-run arms industry, and for Kudrin’s, by advocating “real economic freedom” for every individual and declaring his admiration for “start-ups”. In any case, Putin has so far put economic policy in the hands of the political establishment’s liberal wing – although the conviction of former economics minister Alexey Ulyukaev in December 2017 on corruption charges (having fallen foul of a scheme by long-standing Putin confidant and Rosneft boss Igor Sechin) shines a light on the true balance of power and allegiances in the president’s inner circle.

In spite of the victims of corruption – some of them important personalities – that are regularly paraded before the population, for most people in Russia these are simply the games played by the ruling classes. Their impact is lessened by the fact that in recent years, the population has felt the full force of what lies behind the grim economic figures. What is more, the prospects of any improvement to their situation are just as dim as the growth outlook. Although unemployment is relatively low at 5 percent, so are real disposable income levels, which have reverted to their 2007 levels of around $500. As a result, even Putin concedes that in recent years the share of the population living below the poverty line of the minimum subsistence level has risen by 30 percent, from 15 to 20 million.

Using military might to return to the world stage

Although the optimistic faith in progress which gradually emerged during Putin’s first two terms in office has dissipated, it has left behind an important compensation: Russia’s impressive return to the world stage. The euphoric “Krym nash” (“Crimea is ours”) slogan, the solidarity with compatriots in Eastern Ukraine, the alliance with China and the ability to defy both the US and jihadism in Syria in equal measure have not failed to achieve the desired “rallying around the flag” effect. The fact that Russia once again has a discernible and effective voice among major powers has undoubtedly triggered a deep sense of satisfaction in many people after the fall of the Soviet empire. But what is the basis of this new/old role for Russia? The answer is the only two “allies” trusted by Tsar Alexander III back in the late 19th century, the excessive funding of which brought about the downfall of the Soviet Union: “the army and the navy”. Moreover, despite the decisiveness and ability to act displayed by the Kremlin in the Ukraine and Syria conflicts, neither has been resolved, while their political and material costs continue to spiral. It is therefore quit

e conceivable that Russia’s resurgence on the world stage, primarily military in nature, could (once again) turn out to be a double-edged sword in light of its shaky economic foundation.

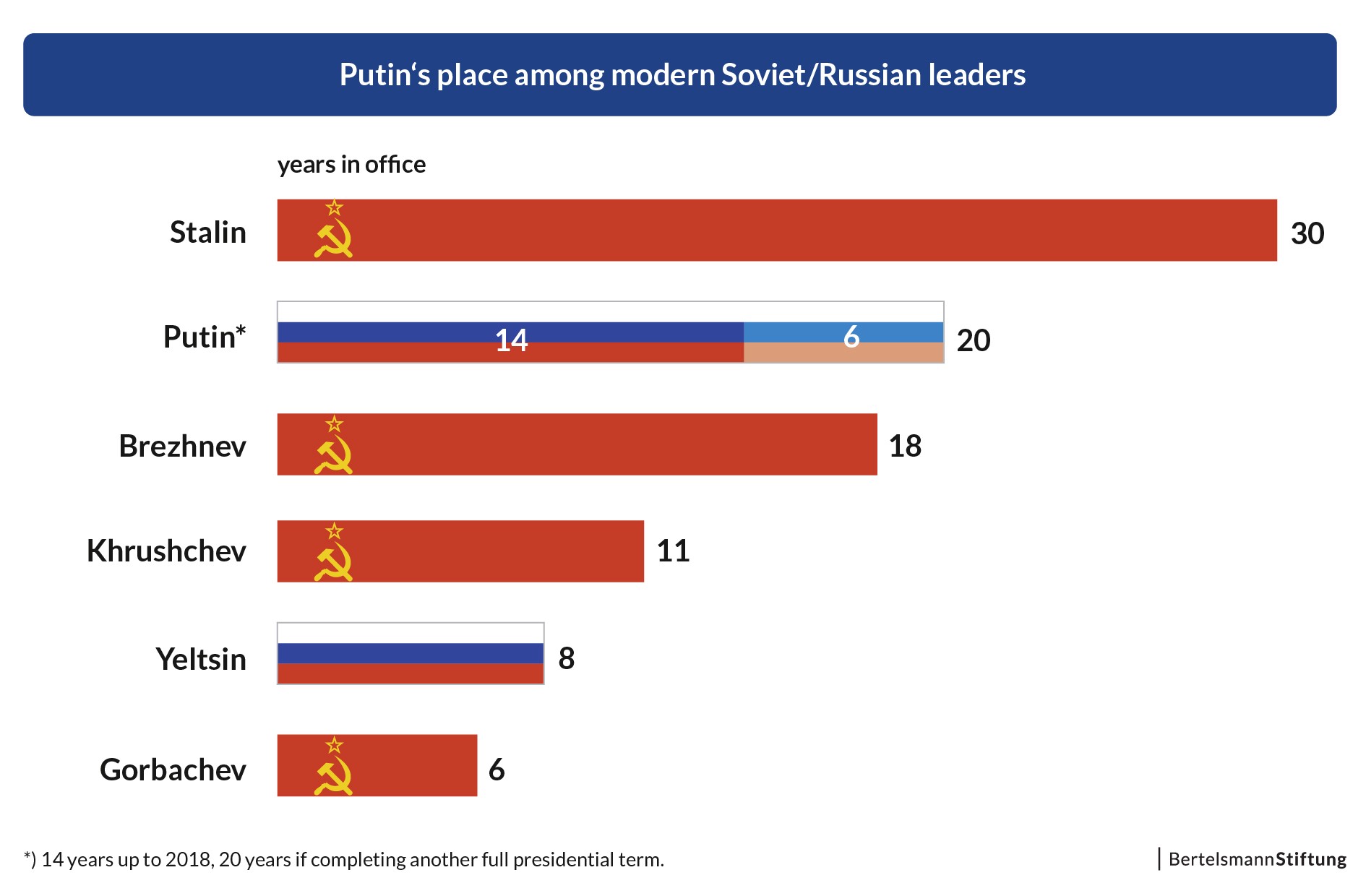

By the end of his fourth term in 2024, Putin will have held office for almost as long as Joseph Stalin, and longer than Leonid Brezhnev.

Despite claims to the contrary in the West, he has clearly distanced himself from the former, for instance when inaugurating the Wall of Grief – an impressive monument to the victims of political repression – in Moscow in October 2017. The latter, meanwhile, could well become a symbol of Putin’s own presidency, as Brezhnev is remembered both for the breakthrough and acknowledgement of the Soviet Union as a world power on the one hand, and for the period of stagnation that heralded its demise on the other. In any event, the rallying cry of “Keep it up!” echoed by all conservatives will only lead Putin’s Russia further into a dead end.

Hans-Joachim Spanger holds a doctorate in political science. He is a program director at the Peace Research Institute Frankfurt and a guest professor at the National Research University – Higher School of Economics in Moscow. He is the author of the regional report “Post-Soviet Eurasia” for the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI).