Revitalizing Democracy in Asia

How can reform-oriented political leaders utilize the rapid social change in Asia and Oceania for their democratic agenda? This question was at the core of a roundtable on “Next Generation Democracy” in Díli, Timor-Leste.

As developing Asia struggles with consolidating their fragile democratic achievements, Timor-Leste is already reckoned by some as democracy’s new poster child in the region. The 1.2-million nation, which achieved independence from Indonesia in 2002 after a long and costly struggle, has recently conducted its fourth parliamentary elections on July 22nd. The elections were held in a peaceful, free and fair manner, and for the first time without supervision by the UN. This prompted former president and Nobel Peace Prize laureate José Ramos-Horta to call democracy “irreversible” in an interview with BTI Blog. The outcome is as close as competitive elections can possibly produce, with incumbent Prime Minister Gusmão’s center-left CNRT party losing its plurality by a most narrow 1,035-vote-margin (or 0.2%) to Fretilin, the left-wing party associated with the resistance against Indonesian occupation. Three smaller parties also obtained seats in parliament, unleashing a race for new coalitions, credible and sustainable political majorities.

Handy cut-out-and-keep guide to new parliament following #timorleste #Elections2017. pic.twitter.com/3AQMhcXWAm

— Ann Turner (@ferikmalae) August 9, 2017

Exciting times to talk about the future of democracy in the region in Díli, the capital of Timor-Leste. The Club de Madrid, a global association of former democratically elected national leaders, thus chose the ideal place and time for a “Next Generation Democracy” roundtable in Asia. From July 29-31, elder states(wo)men, democracy experts, civil society and youth representatives discussed how democratic actors in the region can respond to mounting challenges. Regional expert assessments of the Bertelsmann Transformation Index set the scene for a productive debate.

Asia and Oceania are home to some of the most profound and rapid social transformations of our time. Economic growth in Asia by far exceeds that of other world regions. Megacities emerged and continue to expand at an unprecedented rate, partly due to demographic pressures and changing economic structures. Information technology has transformed previously fragmented communities into gigantic interconnected spaces within one generation. Civil society has gained strength in most countries of the region. These social transformations have the potential to support and sustain democratic values. But they also proliferate tendencies which may damage democracy and destabilize societies. Add to this existing deep cleavages along ethnic or religious lines within many Asian societies, interventionism by great powers and the irresponsible crisis management by some leaders within and outside Asia.

Asian democracies in crisis

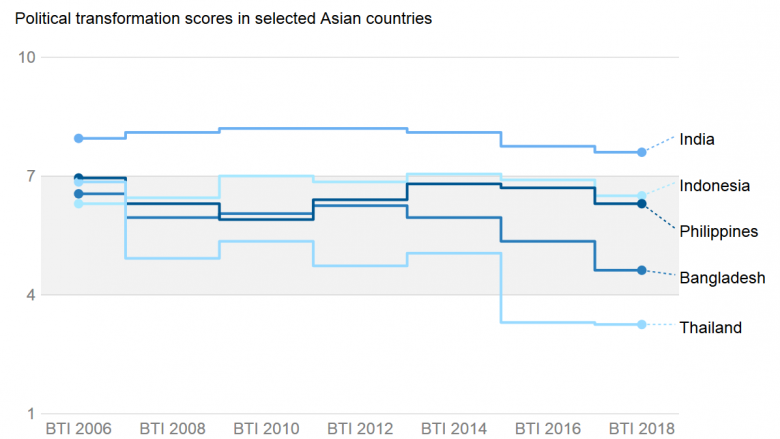

The participants of the roundtable agreed that, evidently, many political systems in Asia are struggling to cope with these multiple challenges. The global trend of democratic deconsolidation has gained a foothold in the world’s most populous region. Bangladesh has been plagued by sectarian violence and extrajudicial killings in recent years. In the Philippines, President Duterte’s war on drugs and crime has caused human rights violations and infringements on civil liberties on a massive scale in the past year. Thailand since 2014 has been subjected to the repressive rule of a military junta that muzzles previously achieved political rights and civil liberties. Even in the two largest democracies of the region, India and Indonesia, nationalists and religious fundamentalists rally up considerable followings with a growing political influence.

Rather than lamenting about the state of affairs, participants of the “Next Generation Democracy” roundtable in Díli were sharing and discussing transformative practices that could halt or even reverse the trend of democratic deconsolidation. Examples include a reporting system by Korea’s finance ministry which collects public input on wasteful spending and budget misappropriations, a TV show in Nepal which highlights and rewards honest and hardworking individuals within a corrupt public sector, and an online data base in Vietnam which compares local authorities’ performance and governance based on surveys with a random selection of citizens. Many transformative practices work at the community level, involve civil society and make small but effective contributions to democracy.

Great closure of the Asia&Pacific roundtable! Our #NGD project's already been 2 years discussing how t advance #democracy worldwide! Thanks! pic.twitter.com/4XGxdRLJjd

— Club de Madrid (@ClubdeMadrid) August 1, 2017

A consensus on peaceful conflict resolution is needed

Another transformative idea was introduced by Timorese youth representatives whom the hosting Ministry of Foreign Affairs enlisted into the conference: a standing youth parliament with 130 democratically elected delegates aged between 12 and 17 from all 13 districts of the country serves as a place of democratic capacity-building and public deliberation over youth affairs for youngsters. In a country where 68% of the population are younger than 25 and the median age is 19, this is a major step towards forming and sustaining democratic values among relevant actors of tomorrow. There was a consensus among the roundtable speakers that discussions on the future of democracy cannot be decided over the youth’s head, but need to involve the youth. The future of democracy in Asia depends on whether future generations have a sense that democratic institutions deliver and work in favor of society.

Yet, for all its charm and praise for its remarkable political achievements in just 15 years, the challenges to Timor-Leste’s defective democracy are not so different from other societies in Asia. By all estimates, Díli has grown from 50,000 inhabitants at the onset of the 21st century to 300,000 today, with many young unemployed men searching for jobs in the capital. Previously isolated villagers have suddenly been connected to the world of Facebook and its likes, creating unprecedented sources of information and misinformation. Civil society has grown stronger especially among the youth which becomes more involved and assertive in democratic politics, yet also susceptible to nationalist reflexes. If only the current consensus among major political actors prevails that peace and stability are to be preserved at all costs, Timor-Leste can resolve the challenges it faces and actually become a standard bearer of democracy in Asia.

Robert Schwarz is Project Manager at the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI). He holds a M.A. degree in Peace and Global Governance from Kyung Hee University’s Graduate Institute of Peace Studies in South Korea and specializes in governance issues in East Asia.