Peace on Earth? The quality of conflict management is in decline

No peaceful Christmas again this year. On the contrary: Not only are wars, civil wars and massive political violence widespread worldwide, but – as explained in the previous blog post – the level of polarization and the intensity of conflicts have, on global average, even increased in recent years.

Which factors are driving the marked rise in conflict intensity, where are polarization or militancy particularly increasing, and which good counter-examples can be identified? In a nutshell: The biggest drivers of increasing polarization are government failure and a diminishing quality of conflict management.

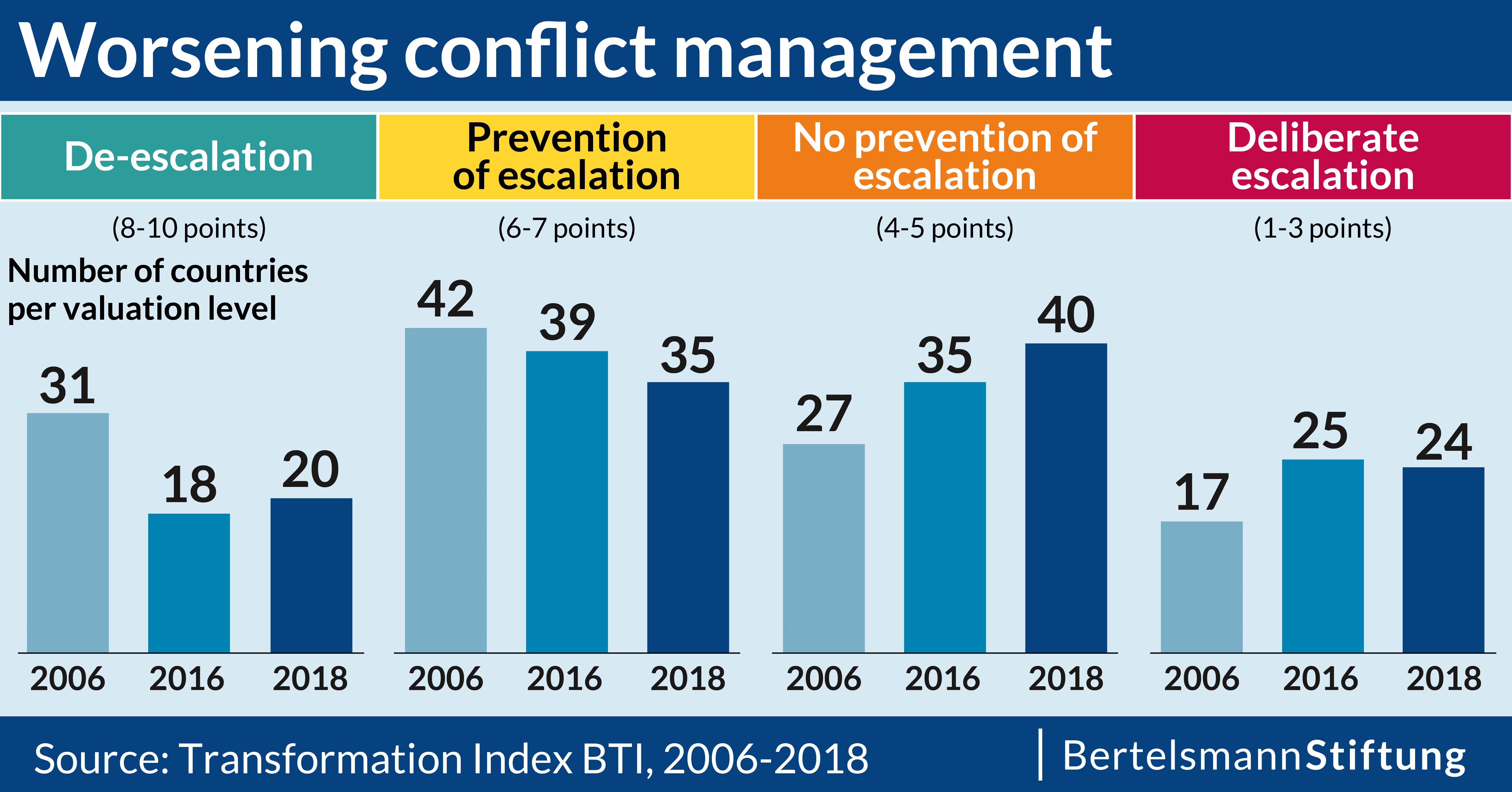

Conflict management is the governance component that has deteriorated the most on global average over the past 12 years. In 57 countries, governments today are less willing or able to defuse social conflicts. As a consequence, in more than half of the countries surveyed, governments are unable to prevent, or even deliberately exacerbate, an escalation of conflicts.

On a scale of 10, the BTI measures the conflict management of governments. The lowest score of 1 point does not solely mean, however, that the government is completely incapable to de-escalate or promote dialogue. Instead, the political leaders rated 1 to 3 points consciously fuel existing conflicts as a strategy to secure power. Only from 4 points upwards is it ascertained whether a government has a positively applied capacity for conflict management, and with what success. This makes it all the more alarming that a whole fifth of all governments in the 119 countries continuously surveyed since 2006 are aggravating conflicts. Another third of the governments surveyed are unable to de-escalate existing conflicts.

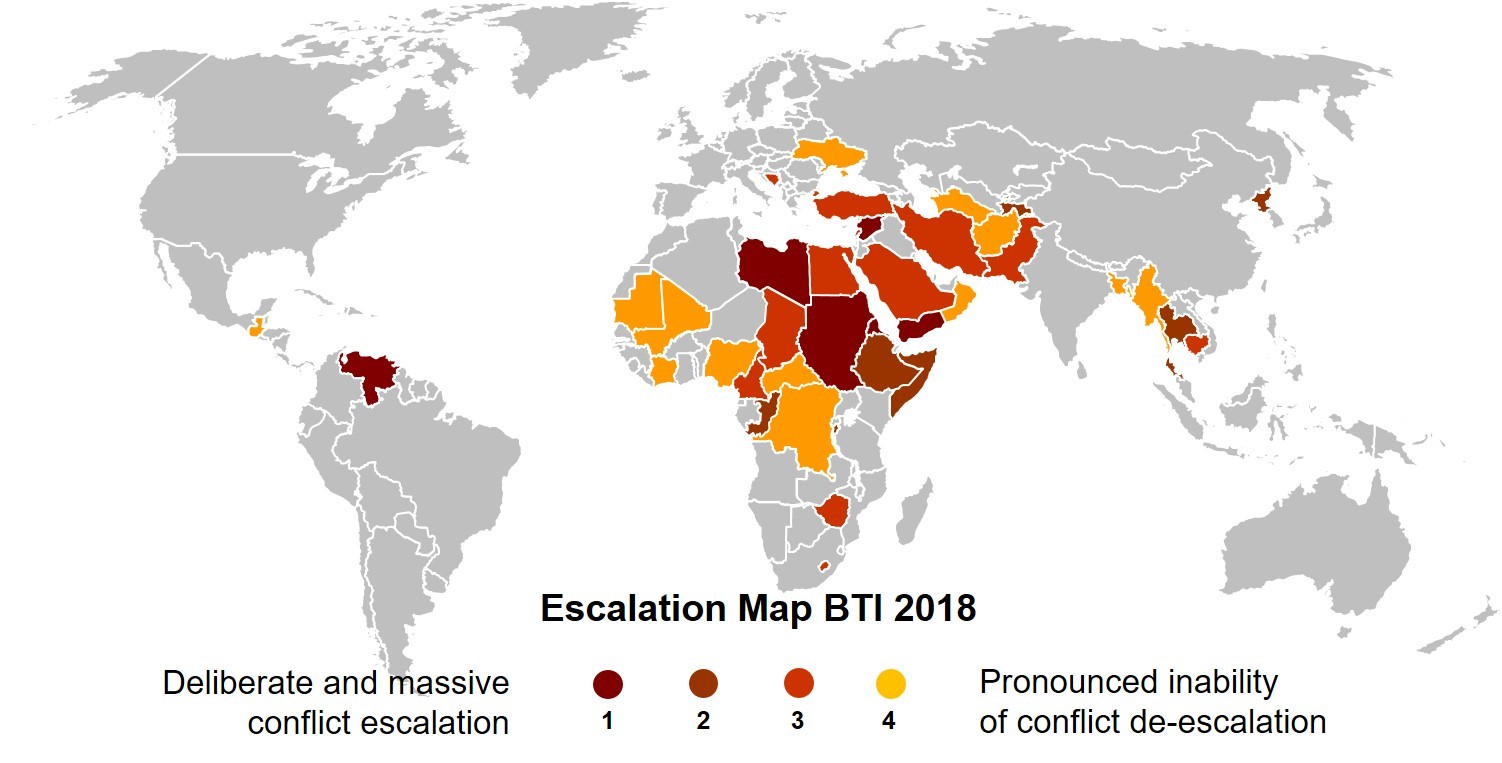

By far the most devastating government performance in dealing with conflicts, including the deliberate intensification of social tensions, can be found in the Middle East and North Africa: violence has escalated in Libya, Syria and Yemen and has reached the almost unchanged high levels of Iraq and Sudan. Why is there so much political violence and so little good conflict management in Arab countries? Too great a role for religion, too early democratization? Let’s take a closer look:

In recent years, the influence of religious dogmas on the legal system and political institutions, as measured by the BTI, has risen sharply on a global average similar to the intensity of conflict. This suggests no coincidental parallelism. Indeed, in two thirds of the 26 countries that show a particularly high level of conflict in the BTI 2018 (7-10 points) a strong influence of religious dogmas can also be recorded. And vice versa: among the 32 countries whose political and legal order is subject to strong religious influence, there are only 11 countries in which social tensions are generally not expressed by violence.

The increase in the influence of religious dogmas generally signals a political instrumentalization of questions of faith, which intensifies polarizations and fuels conflicts. Among the 11 countries with the highest conflict intensity (Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Myanmar, Nigeria, Pakistan, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Ukraine, Yemen), Ukraine is only one country with a minimal influence of religious dogmas. This should neither negate the often peaceful, de-escalating and consensus-building role of religious communities nor the legitimate claim of churches as civil society interest groups to influence political decision-making. If, however, religious principles compete with or even replace secular rule of law, this usually leads to a high intensity of conflict. In recent years, this has been the case especially in the Arab world.

The high level of conflict in this region is often associated with the interim wave of democratization in the wake of the Arab Spring: if the cover of political participation is lifted, so the prejudice, religious extremism spreads in countries without a democratic tradition. The point is misleading. We must remember the many broken reform promises made by authoritarian regimes at the beginning of this century, from the Damascene Spring and the initial Moroccan liberalization under Mohammad VI to the promised yet unfulfilled prospects for freer elections in Bahrain and Egypt. This backlog of reforms exacerbated political tensions, while many disappointed citizens turned to Islamists. Thus, the problem was not the mass political protest movement under the slogan “Bread, Freedom and Dignity,” but a lack of willingness to reform and consensus-building on the part of governments that fomented extremism.

According to recent political experience in the Arab world, stability and declining conflict intensity cannot be achieved by authoritarian governments, but only with more democracy. There is no other region in the world with so many governments that not only do not contribute to solving social conflicts, but deliberately promote their escalation. In 9 out of 16 countries, the power elites obviously have an interest in deepening the social divisions or keeping the existing rifts open. This applies not only to Bahrain, which, with a loss of 6 points in the conflict management indicator, has recorded the greatest deterioration of all countries since the BTI 2006 and where the brutal attacks on the Shiite majority have not subsided in the current assessment period. The regimes in Libya and Syria continue to rely on an escalation of violence. Also in countries such as Egypt and Saudi Arabia, where conflicts within society have increased significantly, governments are not interested in easing the tensions, but instead are increasingly focusing on polarization as a strategy to secure power.

This also endangers the few regional democracies. Take Turkey, for example: Erdogan’s polarizing and confrontational style of government towards activists and supposed sympathisers of the Gülen movement, which after the coup attempt became a newly declared enemy of the government-defined “national interests” alongside the PKK, also classified as a terrorist organization, serves to mobilize and indoctrinate its own followers as well as to exclude all political competitors. Turkey is on the verge of autocracy because of this strategy, which endangers the rule of law and political freedoms.

But the governments’ failure to manage conflict effectively is by no means just an Arab problem. Overall, the situation in sub-Saharan Africa is only slightly better than in the Middle East and North Africa. In 21 of the 38 countries examined there, the willingness and ability of governments to defuse social conflicts has declined since the mid-2000s, most markedly in Eritrea and Mali. The Horn of Africa and the West and Central African regions are also the subregions in which the intensity of conflict is particularly high and the governments’ success in de-escalating is particularly low. Nevertheless, in many West African states in particular, the ability to reduce social tensions has increased significantly in recent years. The trend is much more problematic in many South and East African countries. Even if most of them do not yet appear on the escalation map of failed conflict management, governments in previously highly rated countries such as Madagascar, Namibia, South Africa and Tanzania are now able to deal with social conflicts much less successfully than they were ten years ago.

Where the inability or unwillingness to defuse conflicts increases, the consensus of political actors on socio-political goals erodes, civil society becomes less involved in political decision-making processes, and the influence of anti-democratic veto actors grows. This is also the case in Eastern Central and Southeastern Europe, where the consensus on transformation goals has declined more than anywhere else in a polarized and populist domestic political climate.

In view of this sobering global trend, where should we look to report on successful conflict management? First, there are the governments of Costa Rica and Uruguay, whose consistently high capacity for consensus-building and active de-escalation of social tensions is exemplary and differs markedly positively from the polarizing and escalating course of the regimes in Nicaragua and Venezuela and from the declining quality of conflict management in Brazil and Mexico. Uruguay, under the centre-left government of Frente Amplio, is a prime example of a prudent, solution-oriented policy that actively involves civil society. It is the only country to receive a maximum score of 10 points for its conflict management in the BTI 2018.

Hardly less impressive is the equally consistently good conflict management in Benin, a country with more than 50 different ethnic groups and languages. In addition, there is – as in many West African countries – a latent tension between the more Christian, more densely populated and more industrialized South and the more Islamic and agrarian North. While under the former President Yayi these tensions rose due to an alleged favoritism of the northern part of the country, his successor Patrice Talon, who won the elections at the head of a multi-ethnic coalition, is again increasingly trying to reconcile and strengthen democratic institutions. Some observers, however, interpreted his statement that he no longer relied on ethnic proportionality but on competence when filling government posts as a latent preference for residents of the southern part of the country.

Mongolia has also been a part of the BTI’s top group for good conflict management for years. The role of civil society has increased over the years and the government has actively involved it in decision-making processes. However, social inequality is growing against the background of a pronounced urban-rural divide and provides a breeding ground for populist movements.

Among the 21 countries to which the BTI 2018 attests a good conflict management of 8 to 10 points, Liberia stands out with the strongest improvements in the last 12 years. The successful mediation in identity conflicts is one of the most important achievements of the government, which has also convinced Christian churches to suspend their divisive campaign for the official recognition of Liberia as a “Christian state”. With Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea and Liberia, West Africa has particularly many governments that focus on dialogue, consensus building and conflict prevention. So there are the good examples on the long road to more peace on earth. After all.